Flashback Friday - Heyday of the Nurse Stewardess

Between the 1930s and 1960s, “All aboard” meant it was time to go to work for some in the nursing profession.

During the Depression, many nurses eagerly sought jobs in the “transportation lines”—ships, planes, and trains—looking for new opportunities for their skills. Airlines began employing nurses in the early 1930s; railroads followed suit a few years later.

“Our first duty as stewardess was chiefly to assist mothers in the care of their children.”

Eunice P. Hoevet, a nurse stewardess on the Union Pacific's passenger train Challenger in the 1930s

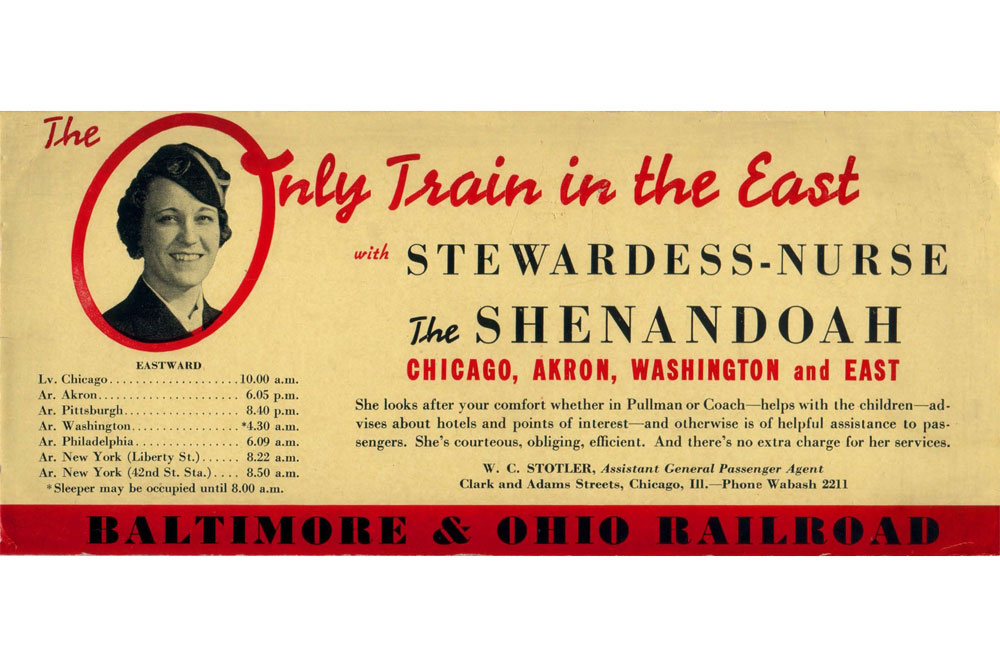

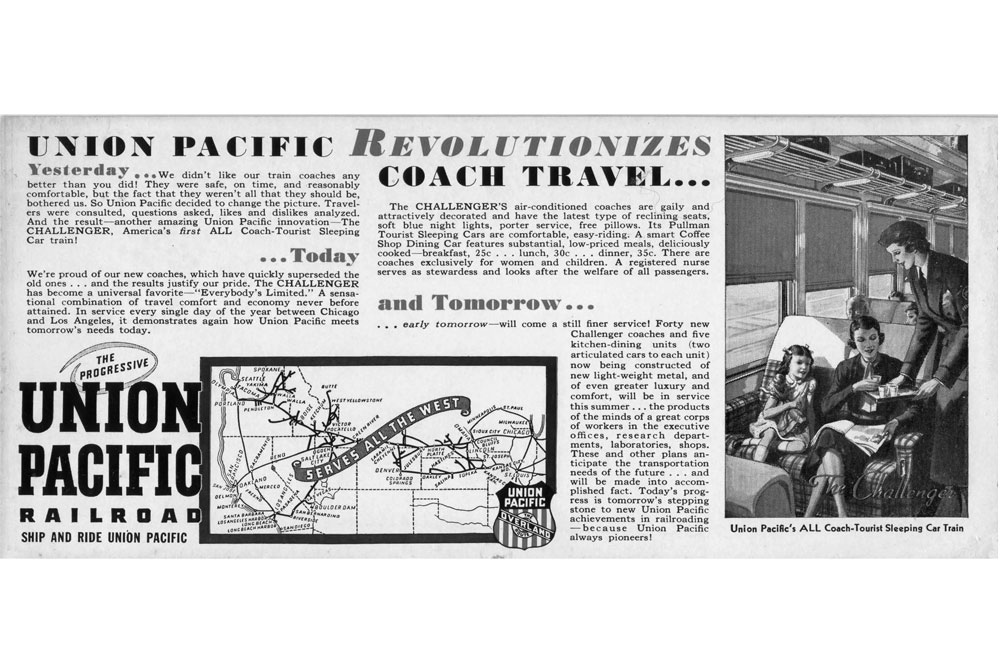

Union Pacific Railroad helped usher in this new branch of public health nursing. In 1935, the railroad hired seven graduate nurses to serve on the Challenger, a deluxe coach train popular with tourists. A splashy brochure hailed the Challenger as “a sensational combination of travel comfort and economy never before attained.” Passengers could expect air conditioning, reclining seats, soft blue lighting, free pillows—plus a registered nurse who served as stewardess and looked after everyone’s welfare.

Interest ran high but openings were few. The lucky minority who fit the mold were young, single and attractive. All had to be female. For the railroad, the physical requirements were highly restrictive: age, 25 to 28; height, from 5’3” to 5’7”; weight, 125 to 145 pounds. Each nurse had to be a registered member of the American Nurses Association. Some companies required them to be able to speak a second language.

By 1938, 326 registered nurses were working for five different airlines, according to a survey by the American Nurses Association. Four railroads employed a total of 94 nurses. In the shipping industry, five employed nurses, but just 12 overall.

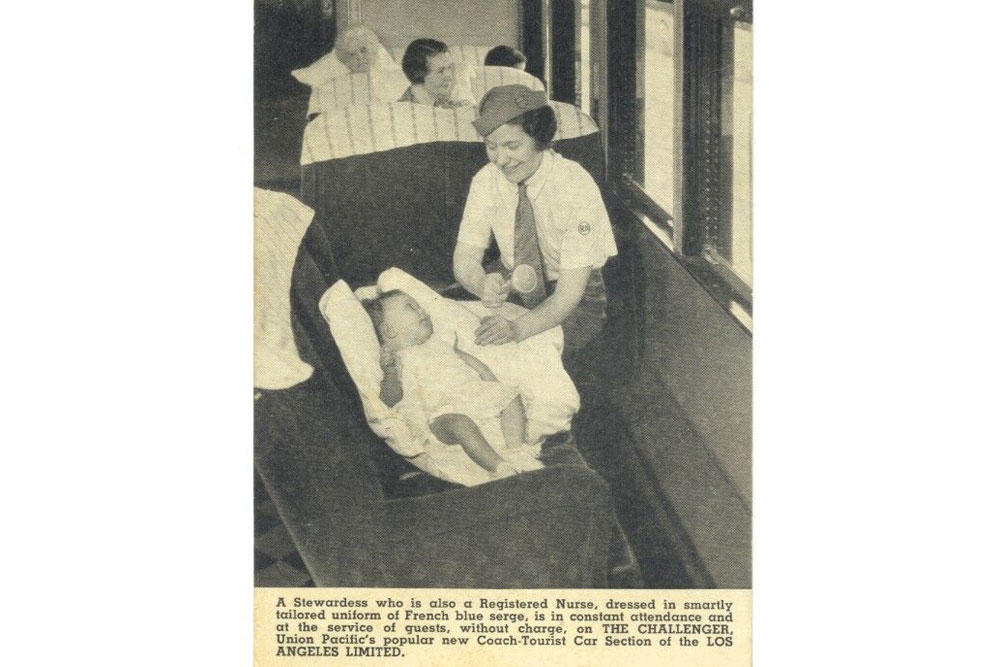

Nurse Eunice P. Hoevet regularly worked marathon schedules on the Challenger, which connected Chicago with Los Angeles. “Our first duty as stewardess was chiefly to assist mothers in the care of their children,” she recalled in a 1937 essay in the American Journal of Nursing. During the summer months, especially, numerous children travelled alone and were under the reassuring care of the nurse stewardess.

As the train wound through Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Nevada, Wyoming, Utah, and California, Hoevet sterilized bottles, prepared formulas, and handled any number of crises. “Each nurse learns to know the different types of formulas prescribed by pediatricians from every section of the country,” she said. Sleeping quarters were in a Pullman car or one of the train lounges exclusively for women and children. While her rest period was from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., she was subject to call at any time. But the job paid well.

When the Northern Pacific began its nurse stewardess program in 1955, Geraldine Yanta joined the staff of its Vista-Dome North Coast Limited, traveling the 4,638-mile round trip between Seattle and Chicago.

Talking with passengers as part of her hostess role, Yanta could evaluate and anticipate the nursing service some passengers would require during the journey. “Some persons may doubt that a nurse can be a real nurse outside of a hospital,” she wrote in a 1958 essay in the American Journal of Nursing. “They forget that all travelers are not rugged and healthy… There are, for example, the cardiac patients who would not be able to travel without professional observation. Postoperative patients, too, frequently return home by train. Often they need special care and reassurance.”

When emergencies arose, the nurse could wire for a doctor, if needed, to come aboard at the next stop. Prescriptions could also be wired ahead and delivered at the next station.

Adaptability was the watchword for the nurse who rode the rails. But there were lighter moments, too, and comedy within the chaos. “Shortly after I joined the Northern Pacific, I accompanied a trainful of dependents of Navy men from Bremerton, Washington, to St. Paul, Minnesota,” Yanta recalled. “There were almost 100 children, most of them under 5 years of age, countless canaries, parakeets, dogs, and cats. At many stops we received reporters, photographers, Navy mothers, Navy personnel, gallons of free ice cream and milk, and disposable diapers.”

This #FlashbackFriday brought to you by the @BjoringCenter for Nursing Historical Inquiry, with special thanks to @AAHNursing president Arlene Keeling, UVA professor emerita, whose book A HISTORY OF PROFESSIONAL NURSING (Springer: 2018) provided the background for this post.