Flashback Friday - Illuminating Belladonna’s Dark Past

Shakespeare’s Juliet likely took it to fake death, and induce catatonia. 14th century Italian women used it in their eyes to get a glassy, “come hither” look. The Romans contaminated their enemies’ food and liquor supplies with it, and until an FDA crackdown in 2010, some infant teething rings and gels laced with it promised to soothe fussy babies.

But make no mistake about it: Belladonna – derived from plant Atropa belladonna, from the nightshade family – can be dangerous and even deadly.

Belladonna (literally ‘beautiful woman’ in Italian), a plant native to southern Europe, is also commonly known as Atropine, named in the mid-1700s for Atropos, the mythical Greek Fate who cuts the thread of life. Derived by drying and creating a powder from the plant’s leaves and berries, it’s been used for pain relief from ancient to modern times, and remains an ingredient in a variety of homeopathic remedies today that promise to soothe everything from inflammatory bowel disease to asthma, hay fever to colds.

Nursing textbooks from the 1920s to the 1950s noted Belladonna’s uses – pain reliever, pupil dilator, a muscle relaxant, and respiration booster prior to the use of chloroform anesthesia – and careful dosing parameters, as well as the hazards and symptoms when too much is taken.

“It stands on the borderline between central stimulants and central depressants,” says the 1926 nursing text MATERIA MEDICA, by Linette Parker, B.Sc., RN, “because while it stimulates in therapeutic doses, if certain rather narrow limits of dosage are exceeded, the stimulation passes to depression, and large doses cause complete depression and paralysis.”

At toxic doses, too much belladonna could cause excitement, dry mouth, intense thirst, elevated body temperature, inability to swallow, and talkativeness (called “belladonna jag”), followed by delirium, paralysis, and coma, according to the nursing text THE USE OF DRUGS (Modell: 1955). It was apparently sometimes even a poison of choice for those with criminal intent, being that “the mental symptoms of chronic atropine poisoning are so slow to develop and so prolonged that they have led to diagnoses of insanity” (Parker: 1926).

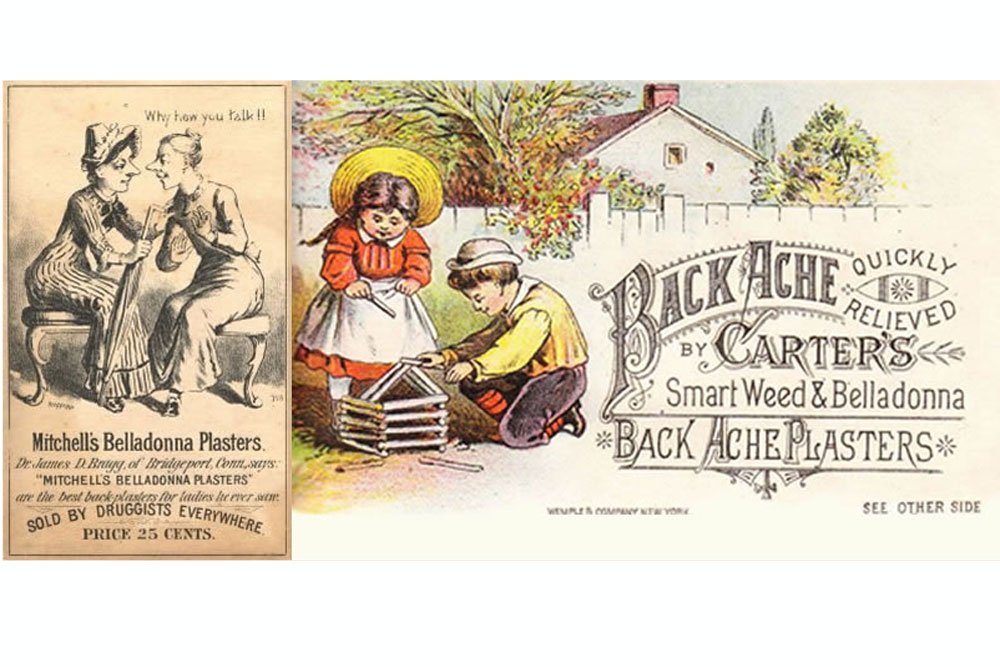

Belladonna paralyzes nerve endings, causing respiration to rise, and body fluids – mucus, gastric juices, and breast milk – to cease production. Patients with asthma, “colic of the bile ducts,” and “spasms of the heart, bladder and uterus” ingested it for relief, but belladonna could also be used topically as a pain reliever, too. And if a Belladonna plant’s leaves were burned, and the fumes inhaled, it was also said to soothe the hacking of asthmatics and individuals with whooping cough.

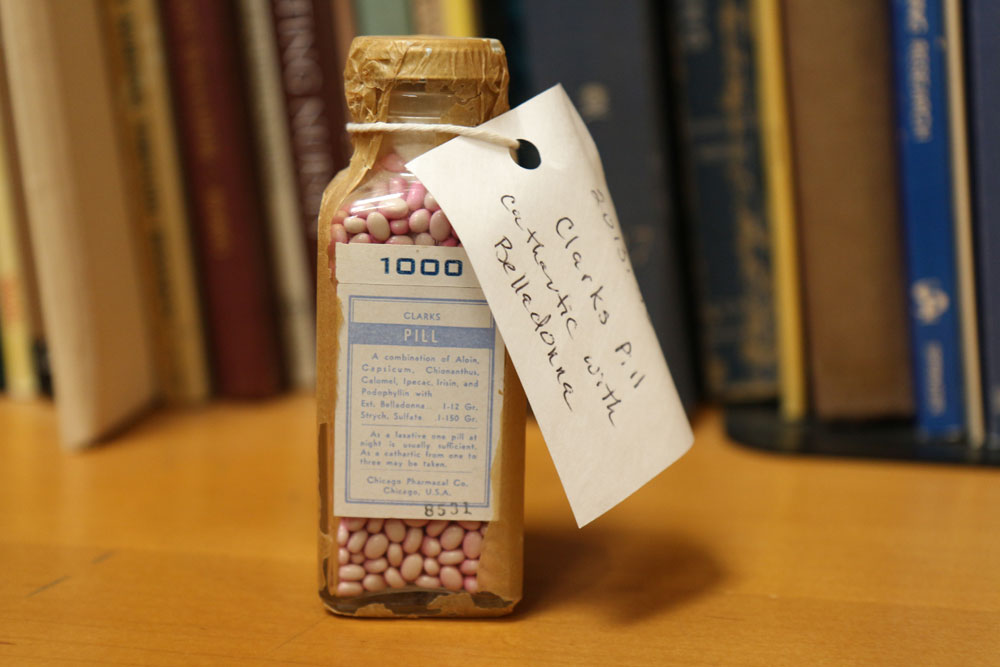

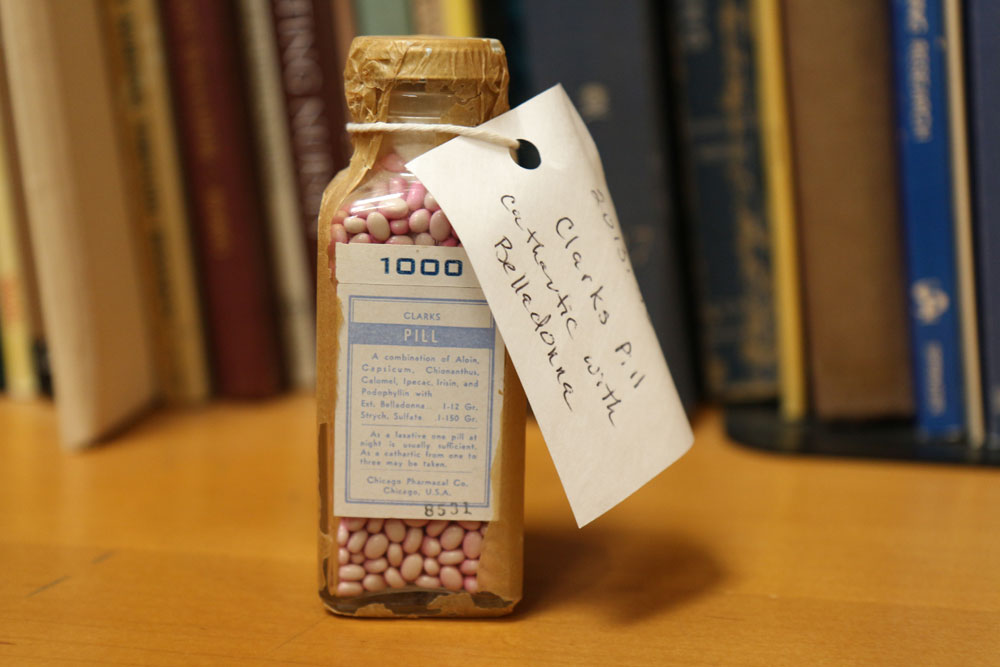

This bottle of “Clarks Pills” from our Bjoring Center archives – used as a nighttime laxative or a purgative – also contained ingredients that seemingly had the opposite effect of belladonna: aloin (a stimulant-laxative), capsicum (an herbal supplement derived from peppers), chionanthus (derived from tree and root bark of the fringe tree), calomel (mercurous chloride, a mineral), ipecac (a plant derivative that induces vomiting), irisin (a hormone), and podophyllin (a resin derived from the May apple plant).

We are unsure of its vintage, though Chicago Pharmacal Co. received patents for medicines as late as 1957 (and paid fines in 1946 for “adulteration and misbranding” their sterile solution Thinoicavin), and was ultimately acquired by Alcon Labs – which specializes today in eye care – in 1962.

Belladonna remains a key ingredient in many homeopathic remedies, and is not regulated by the FDA. According to the National Library of Medicine, there remains “insufficient evidence” that Belladonna is effective for treatments (though it’s still used by optometrists and ophthalmologists to dilate patients’ eyes).

This FlashbackFriday brought to you by the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry. Special thanks to AAHN President @Arlene Keeling, professor emerita.

###