Flashback Friday - Syringe Evolution

Before the advent of plastic, an older generation of nurses delivering medication at the turn of the 20th century through the `40s and `50s used glass syringes exclusively, and were adept at measuring medicines and well-versed in the proper cleaning and sanitizing of the instruments prior to their next use.

Glass syringes, to be sure, had their drawbacks. They were expensive. Fragile. And, perhaps most critically, incredibly time intensive, as they required rigorous cleaning and sterilization between patients. Into the 20th century, nursing students were routinely taught how to use an autoclave, antiseptic solutions and heat exposure to clean syringes and needles during their training. Used glass syringes had to be wrapped in cotton cloth before exposure to heat, however, “to prevent nicking or cracking during the sterilizing process.” When no steam heat under pressure was available, nurses were taught to boil water as a next-best method, as “chemical disinfection should not be used if effective physical means are available.”

A well-made syringe, noted author Bertha Harmer in her 1942 Principles and Practice of Nursing, should “withstand 150 hours of sterilization.” Think of the time these nurses invested!

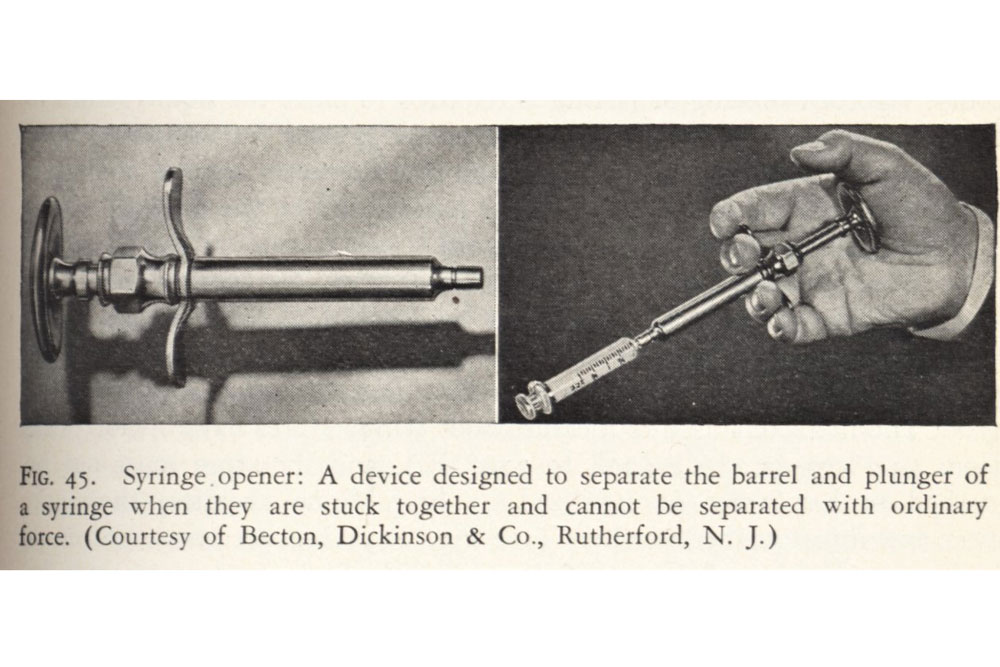

Sometimes, glass syringes would even get stuck together, and require a separate device – called a syringe opener, made of metal – that would be used to separate the barrel from the plunger through force. When no syringe opener was at hand, Harmer advised nurses to boil syringes in a “25 per cent aqueous solution of glycerine [sic] or by allowing it to stand in ether for a few minutes to an hour, depending on the length of time required for the ether to seep between the barrel and the plunger.”

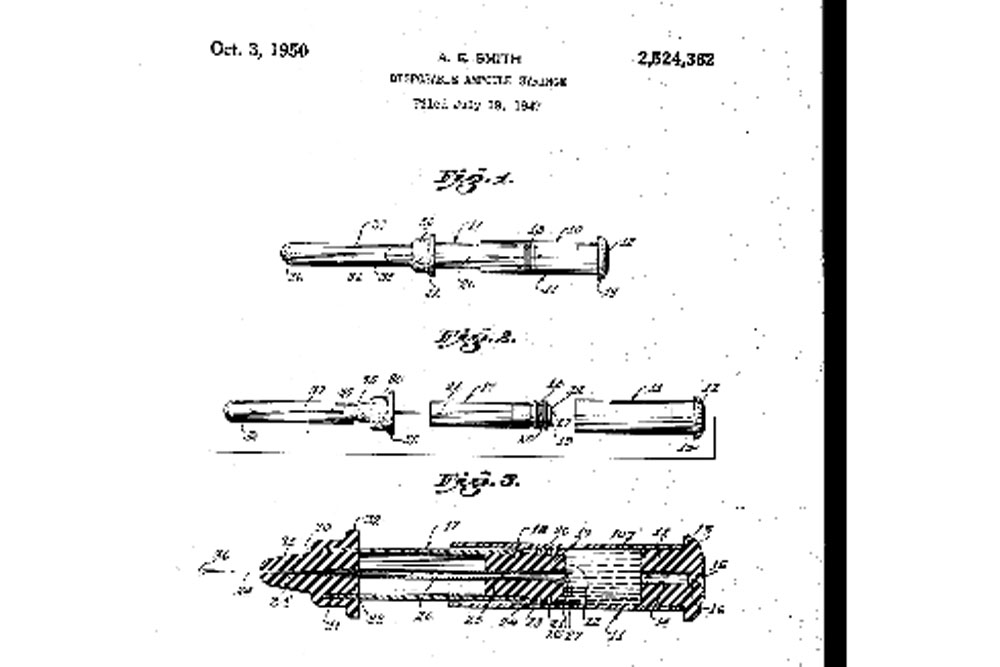

Disposable syringes, then, were a much-welcomed invention. Los Angeles, Ca.-based inventor Arthur E. Smith was the first to create disposable syringes made of glass, netting eight U.S. patents between 1949 and 1950, but it was New Jersey-based Becton, Dickinson and Company (founded in 1897, and known as BD today) that in 1954 first mass-produced them. BD’s famed HYPAK syringe, which administered the polio vaccine to more than a million children, was originally glass. The following year, however, Roehr Products introduced a plastic disposable hypodermic syringe called the Monoject. Cheap and sterile, these were a revelation - and plastic quickly became the standard.

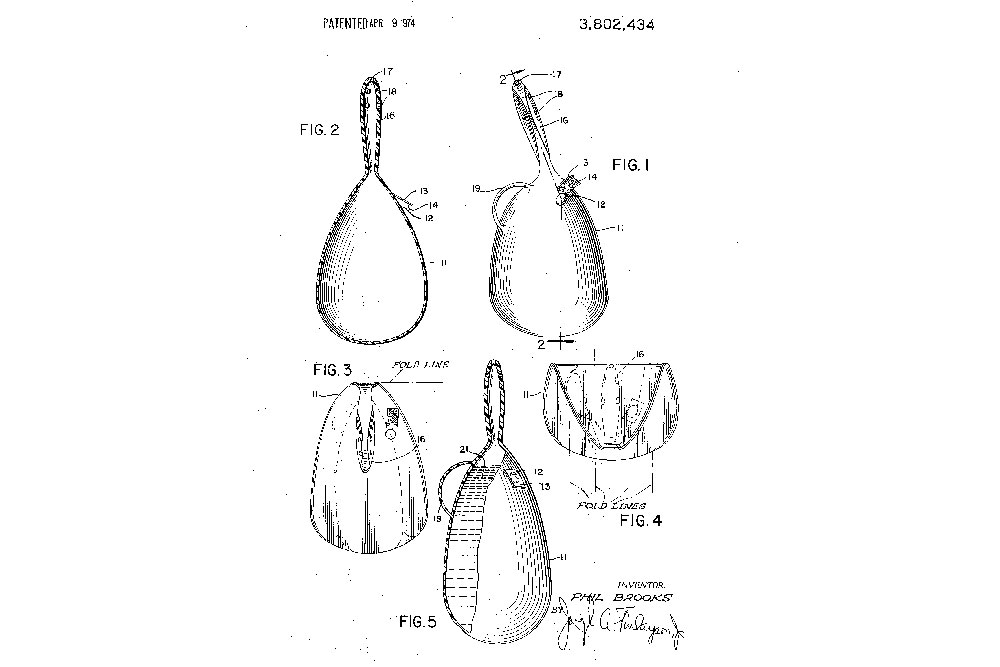

In 1956, New Zealander, veterinarian and pharmacist Colin Murdoch created the first disposable sterile prefilled hypodermic syringe when he was just 27 and looking for an easier way to vaccinate his animal patients. By the time he died in 2008, Murdoch held some 46 patents – including the creation of the world’s first childproof medicine bottle cap – and revolutionized the way syringes were produced and used. Again, it was BD that mass produced Murdoch’s design, creating in 1961 the Plastipak, which is still sold in a variety of forms today. A dozen years later, Kansas-born inventor Phil Brooks – who earned patent #3,802,434 for his “disposable syringe” in 1974 – improved on that design.

###

This Flashback Friday brought to you by the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry. Special thanks to professor emerita Arlene Keeling and Bjoring Center director Barbra Mann Wall and center manager Maura Singleton. Source material includes BD, US Patent Office, Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry QMed Newsletter, and "The Principles and Practice of Nursing" by Bertha Harmer, fourth ed., 1942.