The Painful Past of RN Anesthetists - Flashback Friday

This lawsuit, while not the first challenge to nurse anesthesia practice, signified a serious rift in the cooperative spirit between the medical and nursing professions that had existed since the Civil War, when female volunteers and Catholic sisters assisted with anesthesia. The court’s decision would have lasting implications for nurse-delivered anesthesia for the rest of the century.

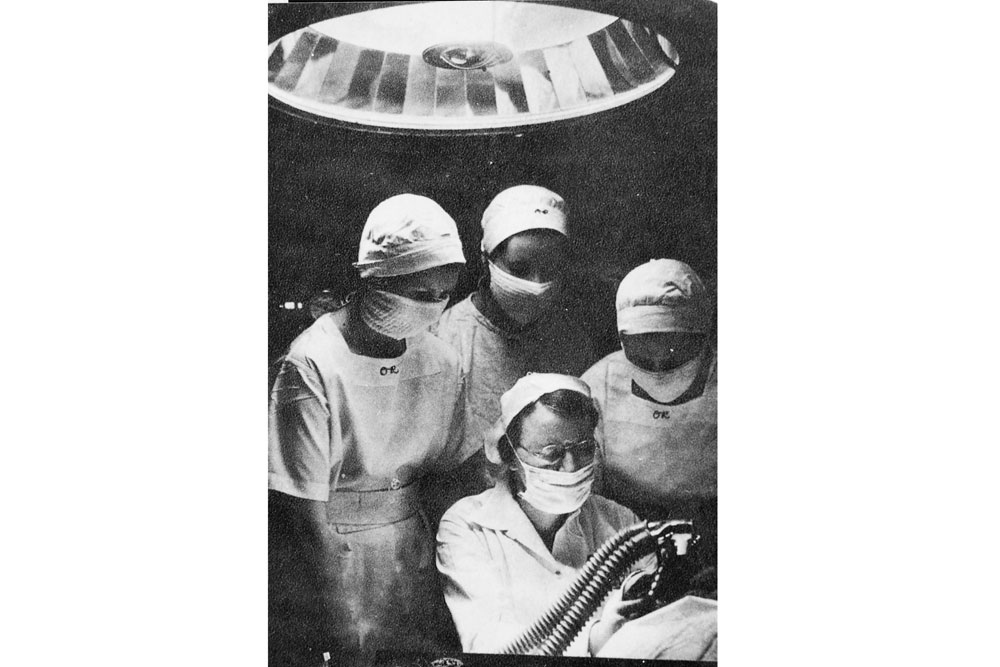

Nurses’ expanded role as anesthetists continued after the Civil War, and developed further during World War I. The 1920s saw a growth in training programs. By the 1930s, there were more than 20 schools for nurse anesthesia across the country that offered six months to a year of post-graduate training.

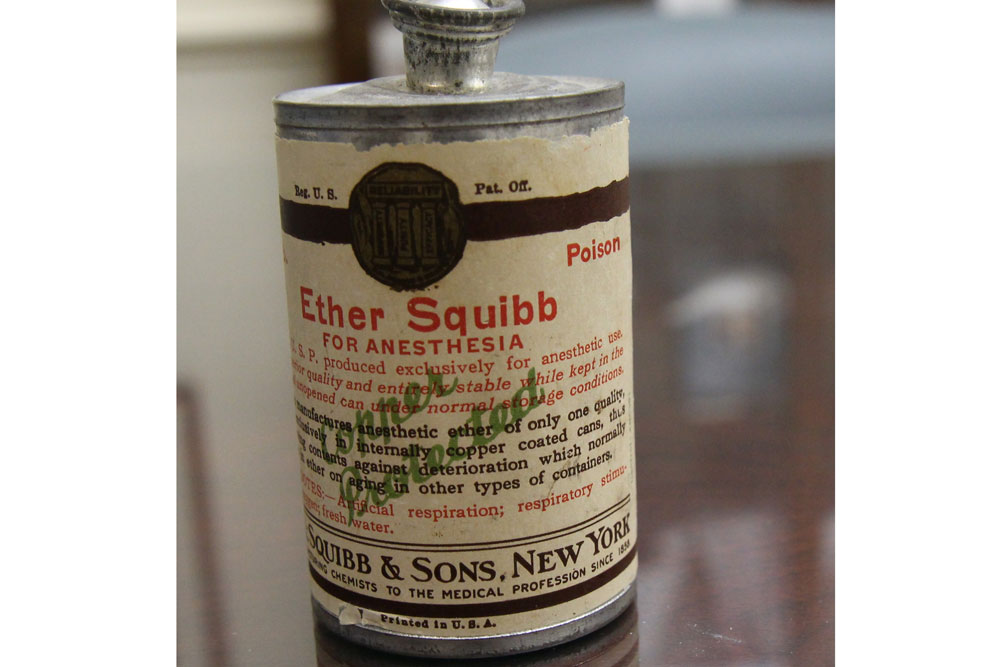

During this same period, however, resistance was mounting. More physicians became interested in this field, particularly with the discovery of new types of anesthesia and new methods of delivery. Giving anesthesia was beginning to require increasingly complex scientific knowledge and clinical skill—becoming, in short, a medical specialty.

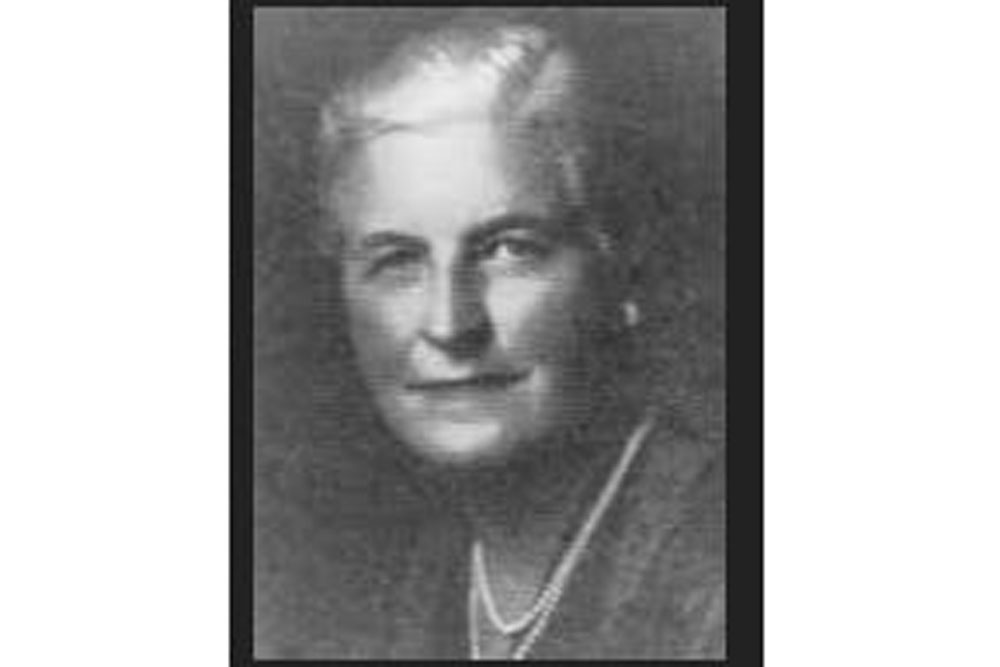

During the Great Depression, tensions between physician anesthetists and nurse anesthetists escalated. When the trial of Dagmar Nelson began in July 1934, the National Association of Nurse Anesthetists submitted a brief arguing that the lawsuit was driven primarily by economic threat: nurse anesthetists were taking work away from physicians.

After twelve days of evidence, the judge decided in Nelson’s favor. He concluded that, “The administration of general anesthetics by the defendant, Dagmar A. Nelson, pursuant to the directions and supervision of duly licensed physicians and surgeons, as shown by the evidence in this case, does not constitute the practice of medicine or surgery … and … constitutes the practice of nursing within the meaning of the laws of the State of California.”

Still, that wasn’t the last word. Dr. Chalmers-Francis filed another suit in 1936, which again resulted in a ruling in favor of nurse anesthetists. Then, in 1938, physicians appealed the case to the California Supreme Court, which upheld the decisions of the lower courts in favor of Nelson. The outcome set a legal precedent for the practice of nurse anesthesia for many years to come. The landmark case became known as “The Captain of the Ship Doctrine,” referring to the fact that the operating surgeon was “captain of his ship” and responsible for everything that happened in the operating room.

The final ruling proved timely. Just a few years later, nurse anesthetists would be in great demand in civilian hospitals and in the military when the U.S. entered World War II.

###

This #FlashbackFriday brought to you by the @BjoringCenter for Nursing Historical Inquiry, with special thanks to AAHN president Arlene Keeling, UVA professor emerita, whose book A HISTORY OF PROFESSIONAL NURSING (Springer: 2018) provided the background for this post. #histnursing #histmedicine