Flashback Friday - Vapo-Cresolene: A Cautionary Tale

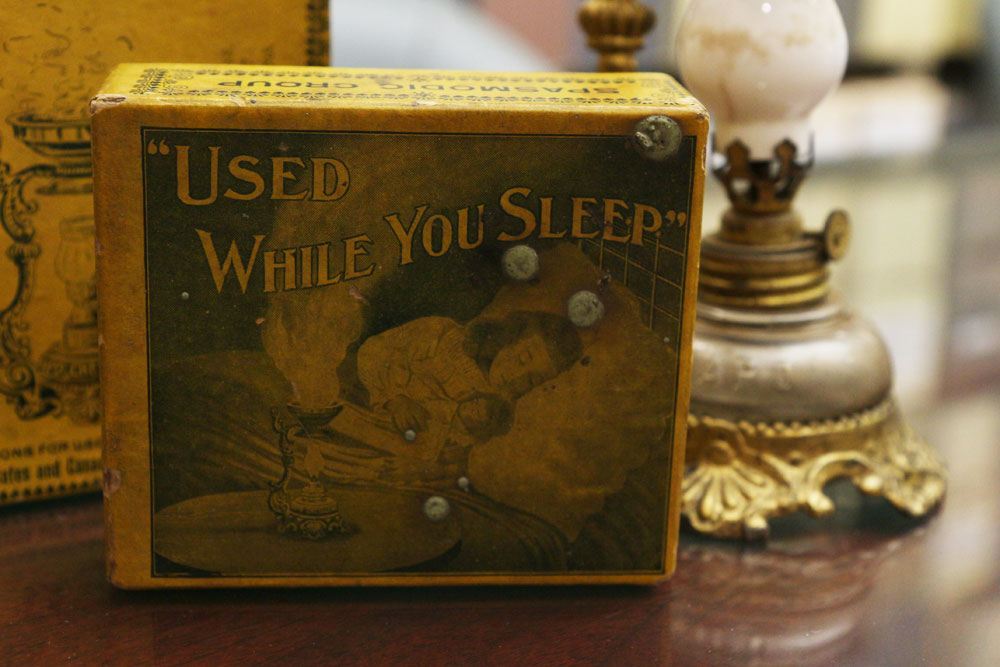

Among the interesting artifacts in the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry is a quaint-looking apparatus in its original box: the Vapo-Cresolene Vaporizer. It shows moderate use. The box, dense with printed information on each side, extolls the powerful germ-destroying properties of this proprietary antiseptic, able to cure “whooping cough, spasmodic croup, nasal catarrh, colds, bronchitis, coughs, sore throat, pneumonia, the paroxysms of asthma and hay fever, the bronchial complications of scarlet fever and measles and as an aid in the treatment of diphtheria and certain inflammatory throat diseases.” Vapo-Cresolene appeared on countless druggists’ shelves beginning in the 1880s, apparently selling well. It also appeared in a national educational campaign known as the “American Chamber of Horrors.”

It’s a reminder of a transitional period in American medicine, before consumer protections, when the public had no way of knowing what was actually in the products they bought. Vapo-Cresolene was patented at a time when university-educated physicians were beginning the struggle to persuade people to use medicines and treatments based on scientific fact, prescribed by licensed physicians, rather than buying “cure-alls” promoted by uneducated, “quack” doctors.

The device used a proprietary formation called Cresolene, a coal-tar byproduct in sticky liquid form that was vaporized over a small lamp lit with kerosene. As early as 1908, the American Medical Association’s analysis concluded that it was a sham, no more effective than generic (and less expensive) cresol: “Vapo-Cresolene is a member of that class of proprietaries in which an ordinary product is endowed, by the manufacturer, with extraordinary virtues.” If used improperly, however, it caused harm. Near poisonings were reported in medical journals when it was used in an improperly ventilated room.

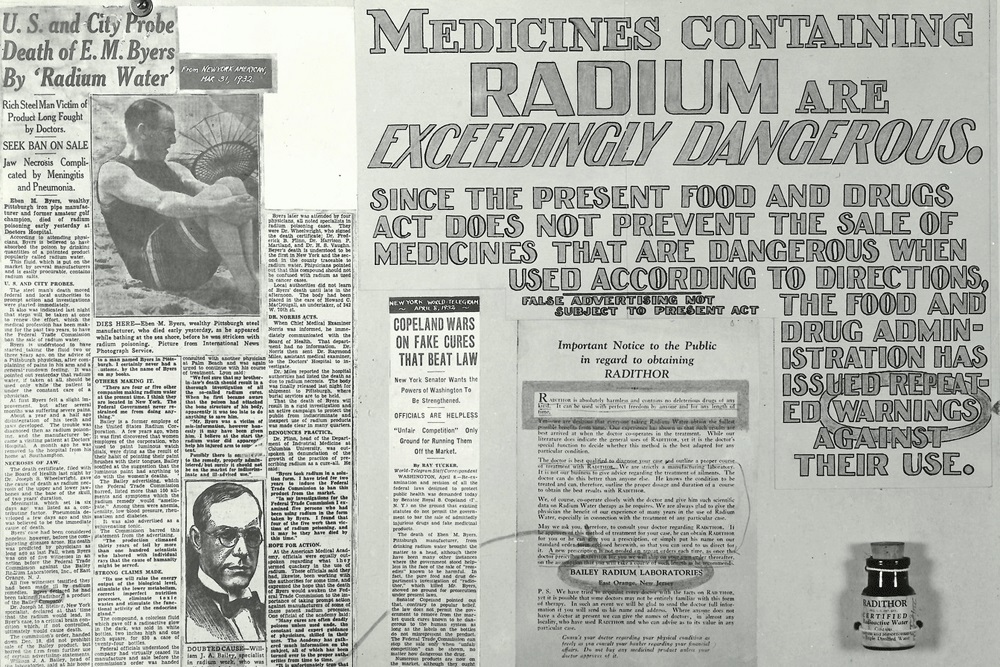

The medical profession pushed hard for legislation to protect the public from patented medicines like Vapo-Cresolene, demanding that their contents be identified and listed on the label. These efforts culminated in the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Essentially a “truth in labeling” law, it required that active ingredients appear on the label of a drug’s packaging and that drugs could not fall below purity levels established by the U.S. Pharmacopeia. Also, labels had to list any of 10 ingredients that were deemed addictive and/or dangerous if they were present, such as alcohol, morphine, opium and cocaine.

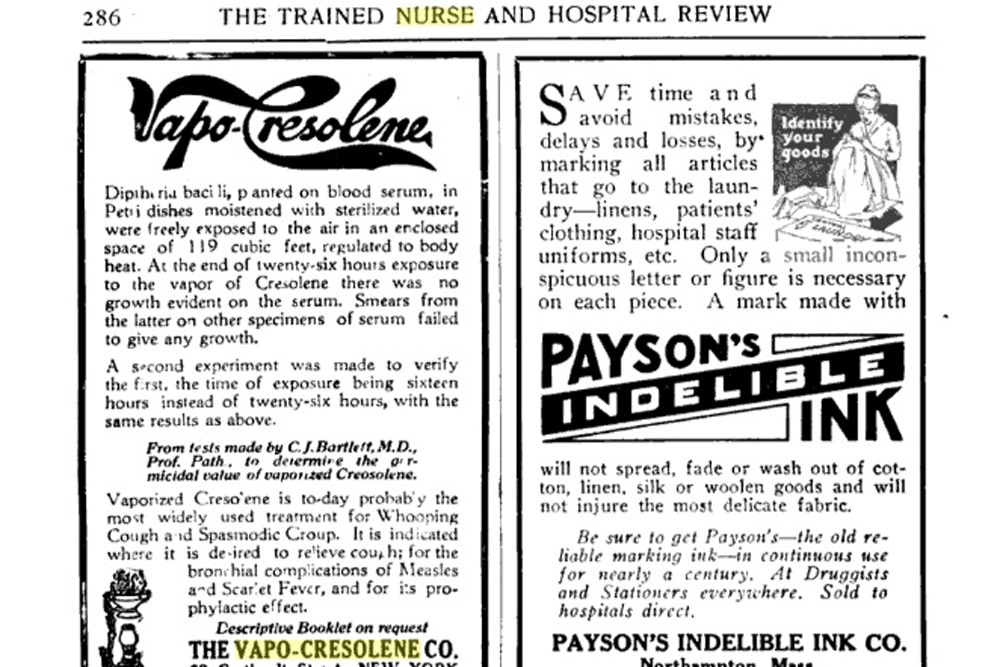

But the law had major shortcomings, and it did little to stop Vapo-Cresolene’s popularity both domestically and abroad. The manufacturer simply transferred its therapeutic claims from the label to advertising. It marketed aggressively in newspapers, magazines, and journals—even The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review.

In 1933, Vapo-Cresolene was among about 100 items in a traveling exhibit so shocking that it was dubbed the “American Chamber of Horrors.” Mounted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it showcased products deemed dangerous, deceptive, or worthless—and which the FDA was powerless to remove from the market. These included quack devices, cosmetics, and radium waters. People saw it at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, at state fairs around the country, and on Capitol Hill. It had its intended effect. Five years later, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 gave the FDA important new authorities and tools to ensure the safety of drugs, cosmetics and devices.

For that all, the Vapo-Cresolene Company showed remarkable staying power. It branched out, offering its product in pill form, and eventually replaced the kerosene lamp with an electric version. It continued to be sold until the 1950s—quite a run for a product proven to be both worthless and potentially dangerous.

This #FlashbackFriday has been brought to you by the @BjoringCenter for Nursing Historical Inquiry, with special thanks to @AAHNursing president Arlene Keeling, UVA professor emerita, whose book Nursing and the Privilege of Prescription, 1893-2000 (Ohio State University Press: 2007) provided background for this post. Photos courtesy of the FDA and Bjoring History Center.