Creating Artificial Intelligence 'In Full Color'

Artificial intelligence—or AI for short—is everywhere, informing how we interact with the world, especially as consumers. But AI is also a growing force in healthcare, and, if properly leveraged, has the potential to both improve patient care and outcomes, particularly for critically ill populations at risk for deterioration or emergent events.

"AI informed by data from homogenous populations poorly generalize. That's why diverse approaches in healthcare, AI included, are so critical."

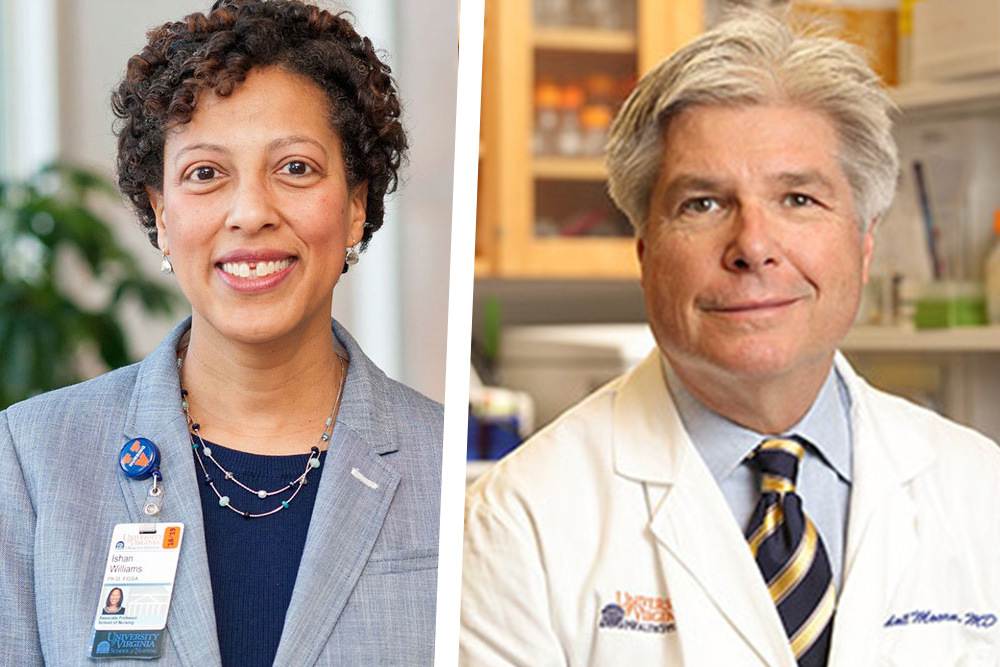

Ishan Williams, associate professor, social, and behavioral scientist and co-PI on a new $5.9M NIH grant

But AI’s promise remains unfulfilled until an “ecosystem”—a method to make meaning out of the wash of numbers that represent a patient’s vital signs—is developed, a critical first step to ensure that AI data is both trustworthy and actionable: precisely the aim a new $5.9 million National Institutes of Health grant earned by co-primary investigators Ishan Williams, an associate professor of nursing, a social and behavioral scientist and dementia scholar, and Randall Moorman, a UVA Health cardiologist and creator of CoMET, along with primary investigator Eric Rosenthal from Massachusetts General Hospital.

The new grant—"Patient-Focused Collaborative Hospital Repository Uniting Standards (CHoRUS) for Equitable AI”—will develop a publicly available, AI-ready critical care dataset of unprecedented diversity, while ensuring methods that promote privacy, accountability, clinical benefit, and equity to a broad, new generation of AI clinicians and scientists.

The volume of patient data pumping through American hospitals is inconceivably vast. Useful datum, what data scientists call “high-resolution data,” make meaning out of numbers depending on context. From intracranial pressure readings to respiration and blood pressure rates, these numbers yield important clues that, in aggregate, can help clinicians provide care in real time, predict adverse events to come, and make astute decisions both quickly and nimbly.

14 petabytes

the number of datapoints streamed by nearly 96,000 ICU beds in 2020 (SCCM; Neurocritical Care)

Rising respiration, heart, and blood pressure rates, for instance, might indicate, on average, a cardiac patient’s possible decompensation, while increases in body temperature, brain activity, and agitation may signal an approaching pain episode for a post-surgical or cancer patient. That high-resolution data in context, the grantees say, is the key to unlocking AI’s ability to phenotype, predict, and quickly make decisions for critically ill patients.

But deriving meaning from AI—essentially creating the rules by which it operates—first requires two important ingredients: a diversity of caregiver perspectives (from nurses, surgeons, respiratory therapists, anesthesiologists, and lab techs, among others) to qualify meanings derived and actionable items to pursue from patient data and ensuring that the data itself comes from patients across racial, ethnic, socio-economic, and geographic domains.

Only then, said Williams, will AI’s promise truly unfold.

“AI informed by data from homogeneous populations of patients and caregivers poorly generalize,” Williams said. “If COVID has taught us anything, it’s that we must take a nuanced, inclusive, equitable approach to everything we do in healthcare, AI included.”

The new grant’s scope and aim—to improve patients’ recovery from acute illness through equitable AI—will bring together scientists and clinicians across specialties determined to make powerful, observable changes at the bedside by deriving meaning out of many tiny numbers. The grant will also establish a consortium so that major medical centers and small hospitals and clinics alike will be able to tap the power and promise of AI.

“AI importantly informs how we care for critically ill patients,” said Marianne Baernholdt, dean of UVA School of Nursing, “but without diverse data at its core, its relevance is limited. This grant, these scholars, and their work will compel that science forward to ensure not only that AI’s building blocks are diverse, but also that its deployment is equitable, accessible, and ubiquitous.”

Acting as co-primary investigators and module leaders, Moorman and Williams will work with grantee co-leaders at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of Florida as well as colleagues from 14 biomedical and clinical organizations, industry, and regulatory agencies across the country. In addition to Williams’s and Moorman’s four awards that will generate new biomedical and behavioral data sets to develop AI technologies, including to the team Williams and Moorman are on, the NIH also administered three “Bridge2AI” awards that will create a central repository to integrate activities and knowledge across data generation projects while disseminating those products, best practices, and training materials.

Williams’s and Moorman’s work began in late 2022; the AI collaborative, training materials, and diverse data sets are expected to be completed by late 2027.

###