Flashback Friday - Please Pass the (Tuning) Fork

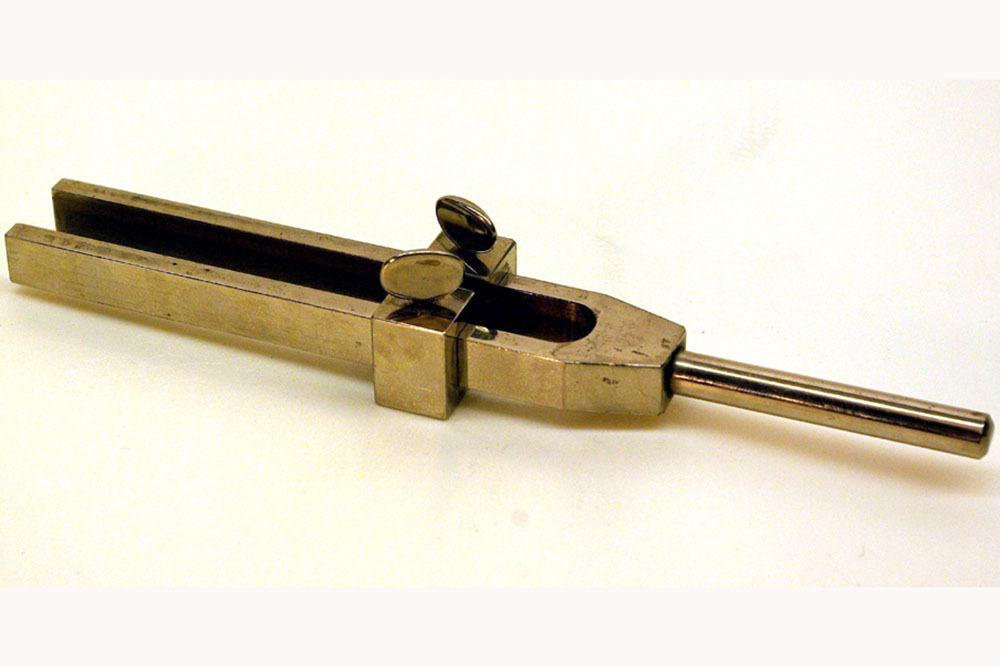

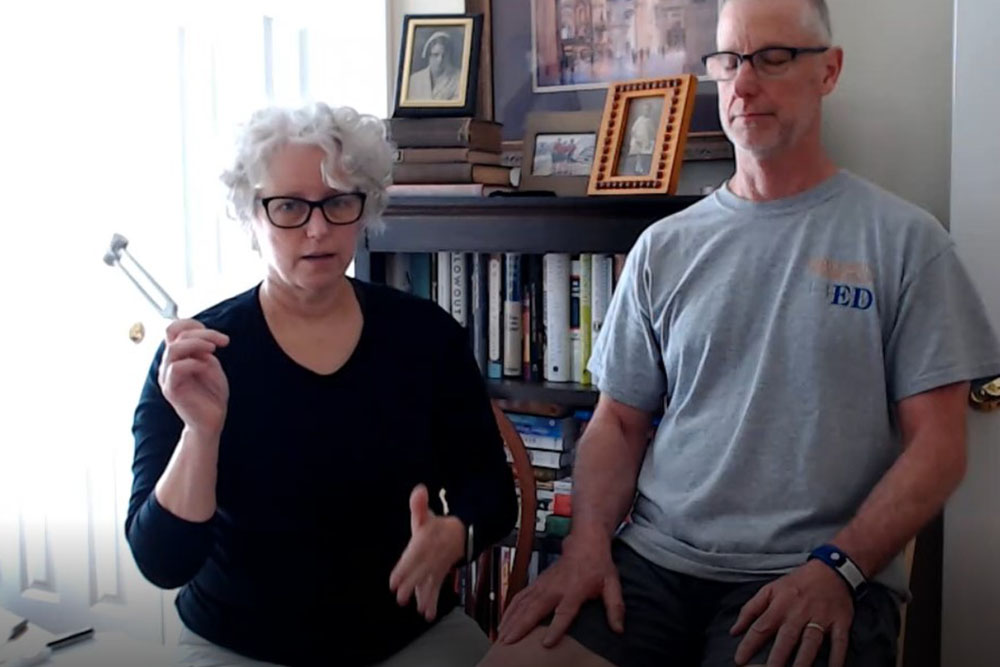

Earlier this summer, advanced practice nursing students received assessment kits in the mail—boxes filled with nursing tools that included otoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, a Rosenbaum chart, measuring tape, and reflex hammers, among other items—to practice their skills during quarantine on loved ones at home following the virtual demonstrations done by their professors. Included in each of these kits were two tuning forks (one that vibrates at 128 hertz and another that vibrates at 512 hertz) devices that, in the twentieth century, have been a nurse practitioner’s go-to apparatus to screen and assess hearing and neurological function.

At the turn of the nineteenth century and today, advanced practice nursing students do the Weber and Rinne Tests to assess whether and what kind of hearing loss is present.

---

Tuning forks themselves, however, have been around much longer. In 1550, Italian physician and mathematician Girolamo (the first person to clinically describe typhus fever and a founding father of algebraic concepts) was the first to describe how sound is perceived through the skull. It wasn’t until 1684 that that idea was operationalized, however, when the aptly-named German physician G. C. Schelhammer used a simple table fork to illustrate the concept. By 1711, British musician John Shore (who played the trumpet and lute) invented the first tuning fork and, by the 1890s, adjustable tuning forks used for teaching health sciences students were introduced.

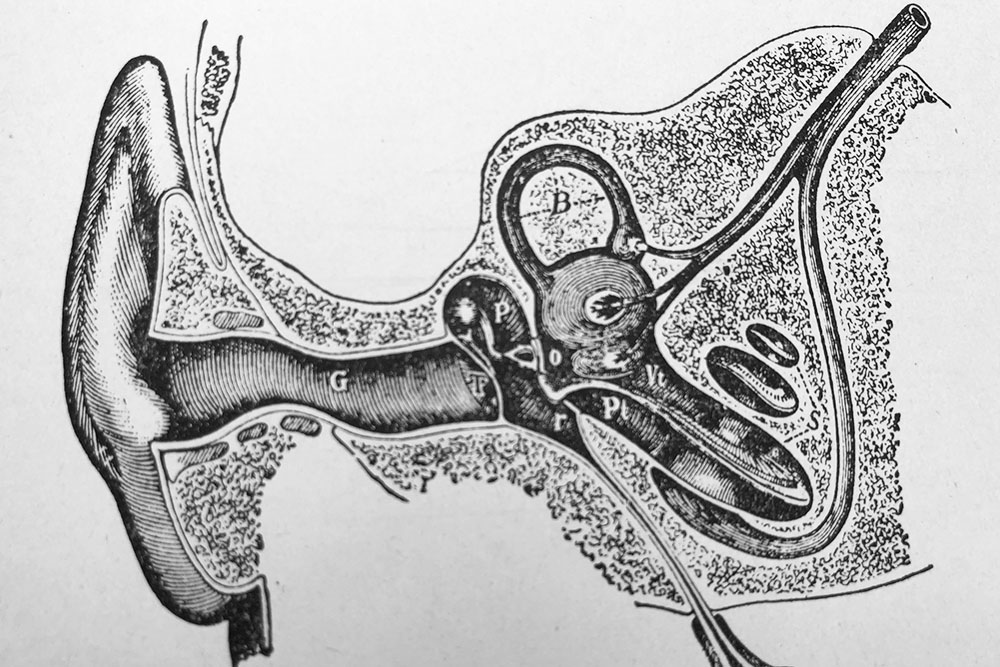

In nursing, tuning forks were used then and now to assess patients’ hearing and, if loss is indicated, to help determine whether the reason for the loss was due to problems with “sound-conducting” or “sound-perceiving.”

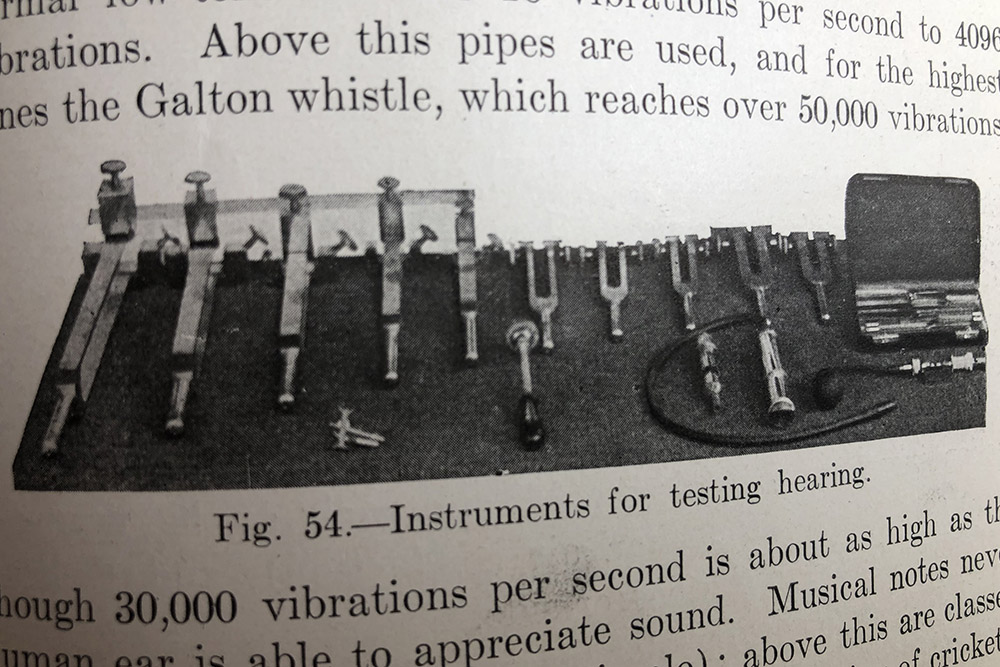

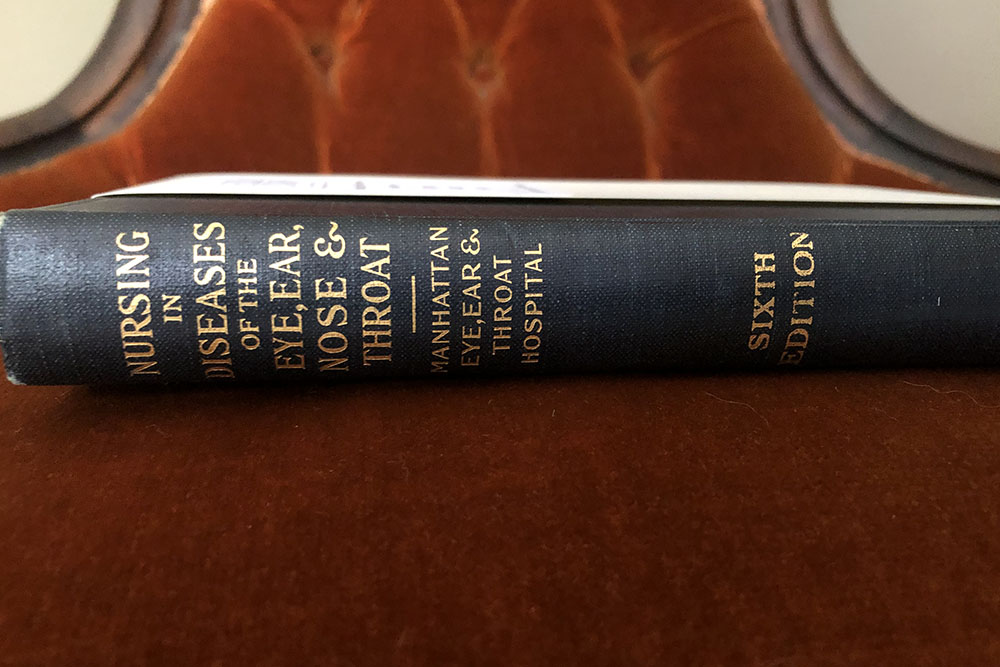

“It is necessary,” assert the authors of the 1937 nursing textbook NURSING IN DISEASES OF THE EYE, EAR, NOSE, AND THROAT (by, among others, registered nurse Mary P. Brown, superintendent of nurses at the training school of the Manhattan Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital), “in testing in the hearing to find tone limits; that is, the lowest and the highest tone a patient can ear, and at the same time note whether he can hear the intermediate tones.”

At the turn of the nineteenth century and today, advanced practice nursing students do the Weber and Rinne Tests to assess whether and what kind of hearing loss is present. The Weber test—in which a nurse strikes a tuning fork and places its stem on the crown of a patient’s head or forehead, equidistant from each ear—assesses whether hearing is better on one side or the other. For the Rinne Test, a nurse places the vibrating tuning fork against the mastoid bone behind the patient’s ear for a few seconds, then moves it in front of the ear canal. In each position, the patient indicates whether they hear the sound, and signal when they perceive that the sound stops. In a healthy ear, conduction of sound through air should be greater than perception of sound through bone. The Rinne, therefore, helps nurses determine whether hearing loss is indicated, and refer the patient to an appropriate specialist if it is.

Tuning forks are also useful in assessing a patient’s loss of neurologic sensation, explained assistant professor Beth Hundt. A vibrating tuning fork—touched to a patient’s extremities while her eyes are closed (usually a distal joint, said Hundt, like the fingers or toes)—can help a nurse determine whether a patient has neuropathy or a spinal injury. A loss of sensation, Hundt said, may be caused by a chronic illness, like diabetes, older age, or even a side-effect of medication, like chemotherapy.

Tuning forks even come in handy if a broken bone is suspected and an X-ray machine is not available. Many also believe that tuning forks are useful in promoting concentration and relaxation through the use of sound therapy.

For nurse practitioner students learning at home this spring and summer, the forks and other nursing tools proved a fun way to practice and hone their assessment skills even under quarantine.

“We sent them the stuff,” laughed Hundt, “but they bring their keen sense of observation and lots of knowledge.”

---

Today’s #FlashbackFriday brought to you by the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry, one of four nursing history archives in the world. Sources include prof. Beth Hundt, the Smithsonian Museum, and “The History of the Tuning-Fork,” (1997). Laryngorhinootologie, 76(2), 116-22. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-997398.