Flashback Friday - The Truths We Uphold?

We are re-posting the following column with the kind permission of professor emerita Arlene Keeling, president of the American Association for the History of Nursing.

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

- The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

As July 4th approaches, I have to say I am struggling to write this message. Does the United States still uphold these truths? I’ve just finished reading Charles M. Blow’s opinion column in the The New York Times, and another by Riane Rolden in the Texas Tribune, describing the appalling conditions in the immigration detention camps. Babies, separated from family caregivers, have no diapers; 14-year-old children are caring for toddlers; and, according to the reports, there are no cribs or beds, no clean clothes, no toothbrushes, and no soap. Already, six migrant children have died in U.S. custody.

"Yes, our government has a history of detaining those whom it fears."

Nurse historian and professor emerita Arlene Keeling, in a letter to AAHN members

I am overwhelmed with a desire to DO something concrete to help these children, instead of writing a column. In fact, I was ready to suggest that all AAHN members bring toothbrushes, soap, and diapers to our annual meeting in September in Dallas so that we could do something as an association, only to find out that border patrol agents will not accept these items, that the camps are all five to eight hours away from Dallas by car (making delivery difficult), and, within 24 hours of this writing, that the children have been moved from the facility.

I have no doubt, however, that terrible conditions in the immigrant detention centers persist, and epidemics will follow. An immigration detention facility in Farmville, Va., has cancelled all family visitations, citing an outbreak of mumps. A recent flu outbreak at the McAllan, Texas, facility sent five infants to the NICU, and a physician who visited described conditions as “tantamount to intentionally causing the spread of disease.”

I would have preferred to write that this type of treatment would never have happened in our nation’s past, but yes, our government has a history of detaining those whom it fears. During World War II, the U.S. government interred more than 110,000 Japanese American citizens in 11 camps throughout the country. The contrast between the care provided in the Japanese internment camps and that which is being provided in the immigrant detention centers today, however, is striking.

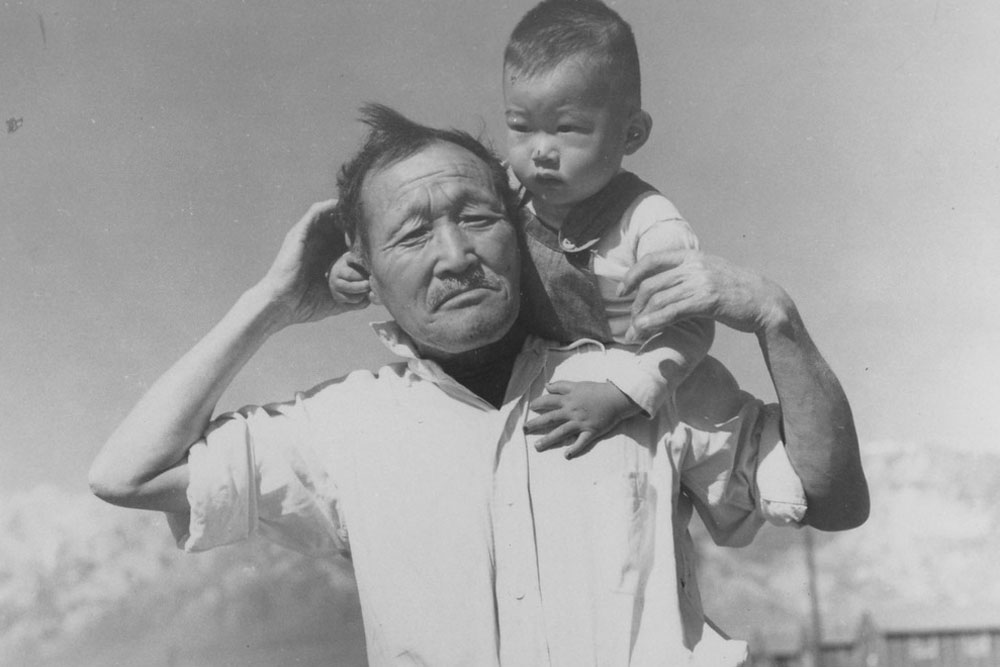

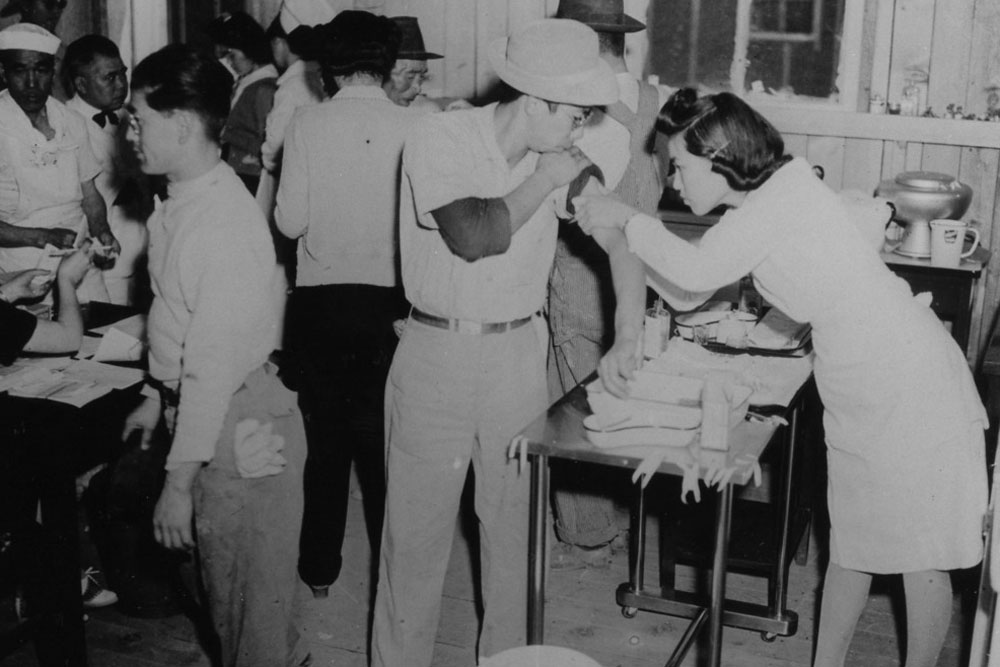

Appalling as it was that the government interred Japanese American citizens, one thing can be said: in that period, the government kept families together and provided basic shelter, hospitals, nurseries, and food. It also recruited Japanese American physicians, nurses, and aides to help government-employed physicians and nurses care for the children.

Analyzing historic government photographs depicting conditions in these camps certainly poses challenges: how much of this documentation was government propaganda? How much was truth? I have examined many photographs from the Library of Congress taken during the Great Depression and the war years. Of those, many capture the realities of awful conditions in the makeshift migrant camps in California in the 1930s. Others, like the photo taken at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, depict better conditions, documenting babies wearing clean pajamas--in cribs with clean sheets--and with a caregiver present. Unlike the recent photographs of the Border Patrol centers today, there are none documenting children living on the floors of cages, without sufficient clothing.

All of this again leaves me frustrated with what actions we, as nurses and historians of nursing, can take. After researching what the American Nurses Association did in response, I found their position statement, condemning the treatment of these migrant children. Perhaps we can write another, supporting the ANA.

I can also recommend that we, together as an association, or as individuals, contribute to organizations like RAICES – based in Texas and providing legal aid to the immigrant children; Save the Children US; or Together Rising.

I welcome any and ALL ideas for making history relevant to today’s issues. I would also like to thank Michelle Chambers Hehman for her contributions to this message.

Arlene W. Keeling, PhD, RN, FAAN

SOURCES

1 Charles M. Blow, “Trump’s Concentration Camps,” The New York Times, June 23, 2019; Riane Rolden, “Lawyer: Inside an immigrant detention center in South Texas, ‘basic hygiene just doesn’t exist,” The Texas Tribune, June 24, 2019

2 https:www.latimes.com/…/la-migrant-child;border-deaths-20190524-s…

3 https://abcnews.go.com/…/doctor-compares-conditions-…/story…)

4 A. Keeling, M. Hehman, & J. Kirchgessner (2018). History of Professional Nursing in the United States:Toward a Culture of Health (Springer: New York).