Essay: COVID Means It's Time to Approve the HPV-Self-Collection Test

Originally published in STAT News May 22, 2020.

Originally published in STAT News May 22, 2020.

My husband, our first-grade child, and I managed to get on what was likely one of the last planes out of Nicaragua the day President Trump banned overseas flights from Europe due to the Covid-19 outbreak. It was an abrupt end to our latest journey to a part of the world where cervical cancer, which I study, often means a premature death with disastrous consequences for the family that is left behind.

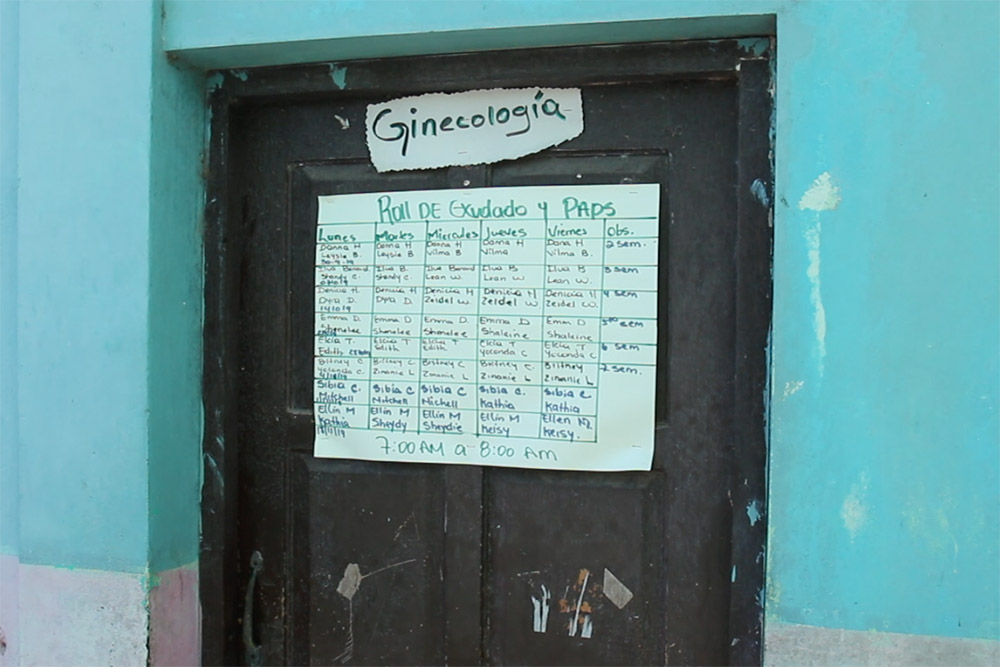

It was difficult to leave Nicaragua — where we have family and friends, and where I have been working an ongoing study — not knowing when we would be able to return. My colleagues, students, and I at UVA have been collaborating for almost a decade with students and faculty at the Bluefields Indian and Caribbean University on community health issues, including cervical cancer.

#1 Killer

Cervical cancer is the leading cause of death among Nicaraguan women ages 15 to 44

I’m a public health nurse who has spent a career studying ways to better test women for the human papillomavirus (HPV), the main cause of cervical cancer, so they can get early and lifesaving treatment. In rural, resource-limited areas — in the U.S. as well as abroad — I’ve seen how this disease claims lives and fractures families. When a mother dies early, stable homes vanish, children are orphaned, and girls’ sexual and reproductive health, often already at significant risk, are placed in even greater jeopardy.

As we flew home that mid-March night, it occurred to me that Covid-19 would rob us of more than its direct victims because it would bring to a screeching halt efforts to check people for preventable diseases like cervical cancer, and treat them if needed.

Covid-19, as we are learning, affects everything. By isolating themselves, mothers, daughters, aunts, and grandmothers don’t see health care providers and end up delaying vaccinations and preventive testing. As Americans comply with social distancing recommendations, there’s been a 73% drop in HPV vaccinations in the U.S. and a 68% decrease in cervical cancer screening. These sharp declines will have serious and long-term effects on vaccine-preventable illnesses.

In countries like Nicaragua, the situation is even more dire. Rates of cervical cancer there are seven times higher than in countries with greater resources. Two-thirds of Nicaraguan women have never had a Pap test, which can provide an early warning of cervical cancer. This cancer is the leading cause of death among Nicaraguan women ages 15 to 44. In the Americas, women in Bolivia and Guyana are at greatest risk of being infected with HPV and subsequently developing cervical cancer, but Nicaraguan women are among the most likely to die of the disease.

More widespread use of an existing, cost-effective testing solution, which can be done at home, could literally change hundreds of thousands of lives in the fight against a disease the WHO has placed in its crosshairs. This will increase our ability to detect women’s risk of developing cervical cancer early.

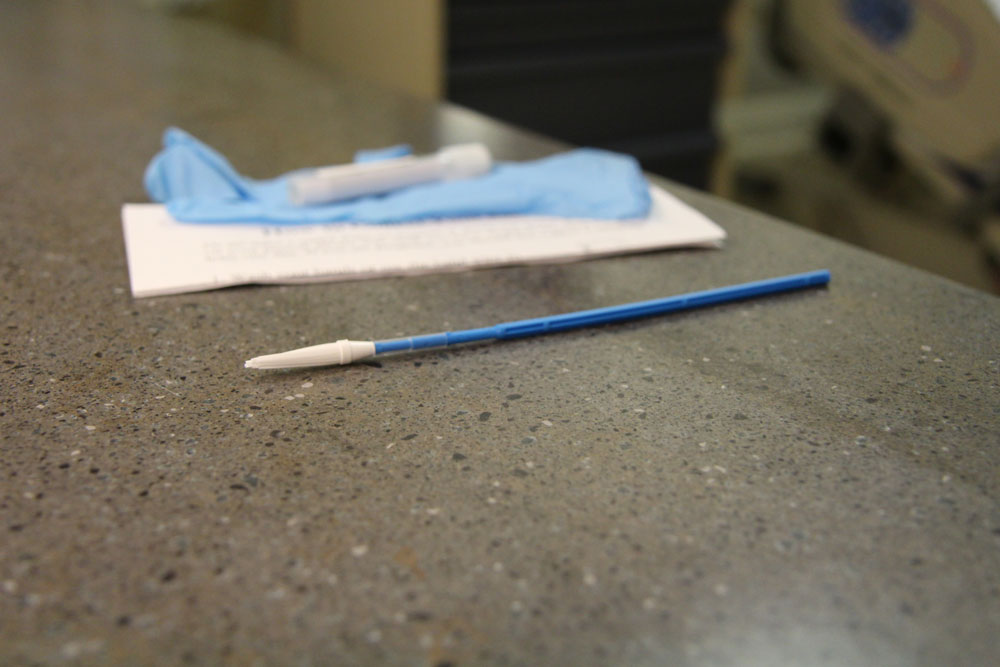

The HPV self-collection test I’ve used in my research in both rural Virginia and Nicaragua makes it possible for women to collect their own cervical sample in the privacy of their homes and mail to a lab to be tested. I urge the Food and Drug Administration to approve at-home self-collection of HPV samples for primary cervical cancer screening it can be more widely available to women who routinely go unscreened. By making home testing kits and follow-up care more available, we can curb the anticipated spike in preventable cervical cancer cases that Covid-19 will inevitably bring.

That first step — approving a kit for women to collect cervical samples at home — has a new and urgent relevance in this era of social distancing. It is a portal through which more women will be saved from cervical cancer, in the U.S. and around the world.

Self-collection tests for HPV are a primary method of testing for cervical cancer across Europe, New Zealand, and Australia. The World Health Organization, which has thrown its weight behind an effort to eradicate cervical cancer, recommends that women self-collect cervical samples for testing whenever possible. It’s time for the United States — where the test is currently approved only for research, even as American women in rural Appalachia die of cervical cancer at rates that are 20% to 33% higher than elsewhere in Virginia — to finally follow suit.

The direct effects of the Covid-19 pandemic are tragic. Its side effects, like creating new disease pathways through reduced vaccination and cancer screening, could be equally harmful. The time has come for the HPV self-collection test to earn a spot as an approved early identification method against this deadly, preventable disease.

Emma Mitchell is a registered nurse, public health nurse scholar, assistant professor of nursing at the University of Virginia School of Nursing, and co-director of the school’s Global Initiatives. Her work in Nicaragua is funded by the University of Virginia’s Global Infectious Diseases Institute.