Shame and Pain: The Physical and Psychic Toll of Lung Cancer

Lung cancer claims the lives of more than 150,000 Americans each year, and accounts for one-fourth of all cancer deaths, making it our nation's leading cancer killer. Though few survive it—just 4.5 to 8 percent of these patients are alive in the five years following their diagnoses—stigma and shame surrounding the disease is rampant.

And though many patients with lung cancer were smokers, even those who never take a puff—like UVA nurse scientist Lee Ann Johnson’s mother, Donna King (below left, with Lee Ann as a toddler), who died of the disease in 2008—often feel chastened by and blamed for their disease. That stigma, Johnson found in her research, not only robs them of quality of life, it makes them less likely to seek relief from palliative and end-of-life care, a tide of suffering Johnson hopes to turn.

Q Your interest in lung cancer is pretty personal.

Q Your interest in lung cancer is pretty personal.

It sounds dramatic, but it’s true. My promise to my mom on her deathbed was that I could “fix lung cancer” (she also made me promise to find a man, buy a house, and have babies). That kept it broad, but I feel like my focus on palliative and end-of-life care for patients with lung cancer fulfills that final promise to her. She is the reason I have my PhD in nursing, and why my dissertation was related to stigma and advanced lung cancer.

When I think about the patients I’m trying to help, I picture my mom and grandfather.

Lee Ann Johnson, assistant professor, nurse scientist

My mom was a never-smoker and, over the years, when I told anyone my mom had or died from lung cancer, the first thing out of their mouth was, “Did she smoke?” With other cancers, the first response is always how the person was sorry for my loss. It became more than an annoyance.

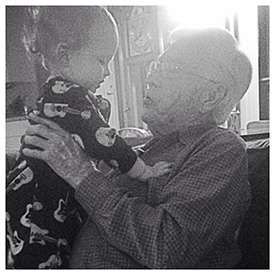

And things came full circle for me. The day I turned in my dissertation, my grandfather, Bob Robinson (at right, with Lee at the Arkansas farm where she grew up), was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. At that point, I'd moved back to Arkansas to care for him while finishing up and defending my dissertation. I used to drive my son around until he fell asleep (he was one at that time, and I also was pregnant) and then work on edits in the McDonald’s parking lot.

the Arkansas farm where she grew up), was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. At that point, I'd moved back to Arkansas to care for him while finishing up and defending my dissertation. I used to drive my son around until he fell asleep (he was one at that time, and I also was pregnant) and then work on edits in the McDonald’s parking lot.

My grandfather—who quit smoking in 1970—died in 2015, a few days after I defended my dissertation, and I’m honestly convinced he held on long enough to see me finish my degree.

How does stigma impact people with lung cancer?

Stigma stirs people’s shame, and prevents them from accessing pain- and symptom-relieving palliative and end-of-life care, even when they desperately need it. And given that advanced lung cancer is almost always terminal—fewer than one in ten people are alive five years after being diagnosed—it’s critical to examine factors that may influence and contribute to their quality of life. They don’t have long to live, and the collective we—their loved ones, nurses, and other care providers—need to make sure that beyond managing their symptoms that their mental and social well-being is intact, too.

You’ve done some research on stigma’s impact on individuals with lung cancer. What did you find?

Previous studies found that between 30 to 95 percent of lung cancer patients felt stigmatized by the disease. I took that work one step further by querying individuals who’d been diagnosed with lung cancer to see whether stigma itself inhibited the care they sought and received, and what specific factors seemed to be associated with that stigma. I received a American Cancer Society grant to fund the research. With that, I asked 62 patients with either stage III or IV lung cancer whether they felt people avoided them because of their cancer, whether they perceived that others looked at them as “less of a person,” and whether they perceived they were to blame for their disease.

READ: Stigma and Quality of Life in Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer [Oncology Nursing Forum, Vol. 46, issue 3]

READ: Stigma and Quality of Life in Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer [Oncology Nursing Forum, Vol. 46, issue 3]

Most were women (37), most were highly educated (27 had at least a college degree), and most reported a history of smoking (41). One-third reported high levels of stigma, a group that also experienced more frequent feelings of distress, depression, and anxiety, fewer meaningful relationships, and less enjoyment of life.

The verdict’s still out on whether the higher-stigma-experiencing patients had a greater symptom burden (more pain, more depression, and so on). It all points to the fact that we clinicians have a lot more work to do to support these patients. Lung cancer-related stigma is generally not part of a typical nursing assessment, but there’s evidence to suggest it’d benefit people, isn’t complex, and can easily incorporated into routine care. It’s exactly the kind of space where a nurse makes every kind of difference.

Q What are the main take-aways from your work?

It’s this: advanced lung cancer has an extremely high symptom burden, but addressing physical symptoms alone won’t improve these individuals’ quality of life. Nurses must be aware that stigma has a serious impact on people, and they can privately assess whether there are ways to improve their quality of life in the time they have left.

Care at the end of life is something every patient and every family benefit from. My personal story is very much intertwined with my research and is what drives my never-ending quest to ‘fix lung cancer.’ When I think about the patients I’m trying to help, I picture my mom and grandfather.

###