$5.9M Grant Supports UVA Research Into the Use of AI in Healthcare

Supported by a new $5.9 million National Institutes of Health grant, two UVA researchers will explore ways to improve the use of artificial intelligence in health care for a wider diversity of patient populations.

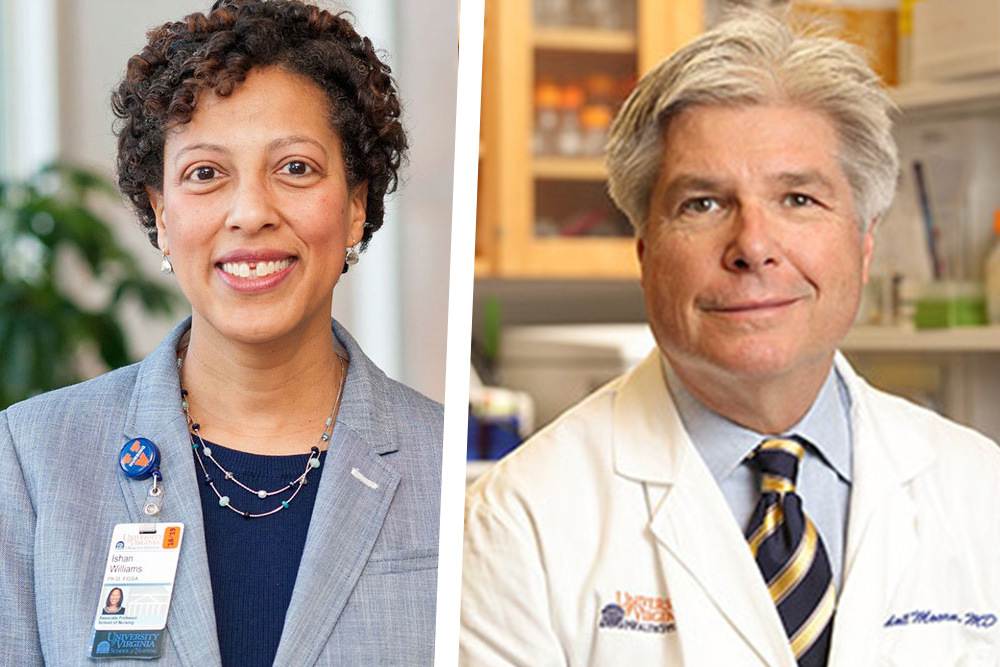

Primary co-investigators Ishan Williams, an associate professor in the School of Nursing, and Randall Moorman, a UVA Health cardiologist, will develop, test, and deploy best practices for artificial intelligence health care systems that aggregate data from a more diverse pool of patients by taking into account their race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and geography.

In a nation with growing racial and ethnic diversity, the effort is a priority for the NIH, which, with its “Bridge to AI” programs, has assembled an array of scholars tasked with its improvement.

“If COVID has taught us anything, it’s that we must take a nuanced, inclusive, equitable approach to everything we do in health care, AI included.”

Ishan Williams, professor, and a public health scientist

COVID-19 has proven particularly vexing for communities of color, which have been, compared to their white peers, devastated by the disease. “If COVID has taught us anything,” Williams said, “it’s that we must take a nuanced, inclusive, equitable approach to everything we do in health care, AI included.”

Acting as co-primary investigators and module leaders, Moorman and Williams will work with investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Florida, and colleagues across the country in biomedical and clinical organizations, industry, and regulatory agencies.

The research could ultimately help increase AI’s ability to play a more effective role in the care of diverse patients.

At many American hospitals, bedside monitors that measure everything from intracranial pressure to heart, respiration, and blood pressure rates feed numbers into AI systems that constantly assesses patients for things like stroke, sepsis, and myocardial infarction.

But because the algorithms that feed predictive healthcare AI systems are often based on homogenous populations, AI that’s meant to improve care sometimes falls short—and may even prove harmful.

Williams’s and Moorman’s work began in late 2022; they expect the AI collaborative, training materials, and diverse data sets to be completed by 2027.

###