Flashback Friday - The 'Bush Nurse' Without Bona Fides

In a 1951 poll, she beat out Eleanor Roosevelt as the woman Americans most admired in the world. Hollywood dramatized her crusading story. There were transatlantic invitations to lecture, honorary degrees conferred. Today, though, Sister Elizabeth Kenny is a forgotten puzzle piece from history.

But in the 1940s, when the United States was gripped by polio epidemics, this Australian nurse with no formal training pioneered a treatment that flew in the face of orthodox practice. Sister Kenny was roundly ridiculed by the mostly male medical establishment, even as her paralyzed patients recovered. The controversy she sparked seemed to fuel her throughout her career.

Before the Salk vaccine was discovered in 1953, recurring polio epidemics overwhelmed communities with fear and dread. Polio, said one parent, was “a word that strikes more terror in the hearts of parents than the atom bomb.”

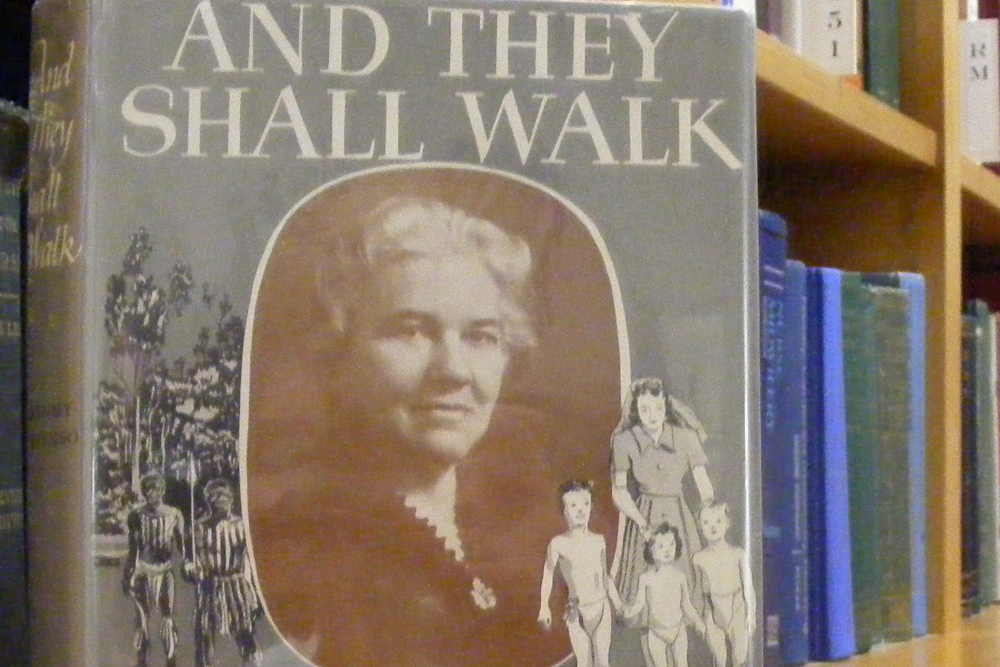

“I was wholly unprepared for the extraordinary attitude of the medical men in its [sic] readiness to condemn anything that smacked of reform or that ran contrary to approved methods of practice.”

Sister Elizabeth Kenny in her 1943 autobiography, And They Shall Walk

This viral disease was also called “infantile paralysis” because infants and children were usually the victims. Those severely affected developed fever and body aches, which progressed to varying degrees of paralysis in a matter of hours or days. In the most serious cases, patients suffered nerve damage to the spinal cord or brain stem and required an iron lung (an early version of the respirator) to help them breathe. The odds for recovery were bleak: five percent to 10 percent of paralyzed polio patients died, and as many as half had persistent partial paralysis.

The conventional treatment called for splints and braces to immobilize paralyzed limbs. Physicians believed that rest protected the damaged limbs. Muscle shortening was treated through surgery.

Enter Sister Kenny. A nun she was not. Largely self-taught, she gained additional experience as a staff nurse in the Australian Army Nursing Service during World War I, serving on troopships. Promoted to “Sister,” she used the honorific for the rest of her life.

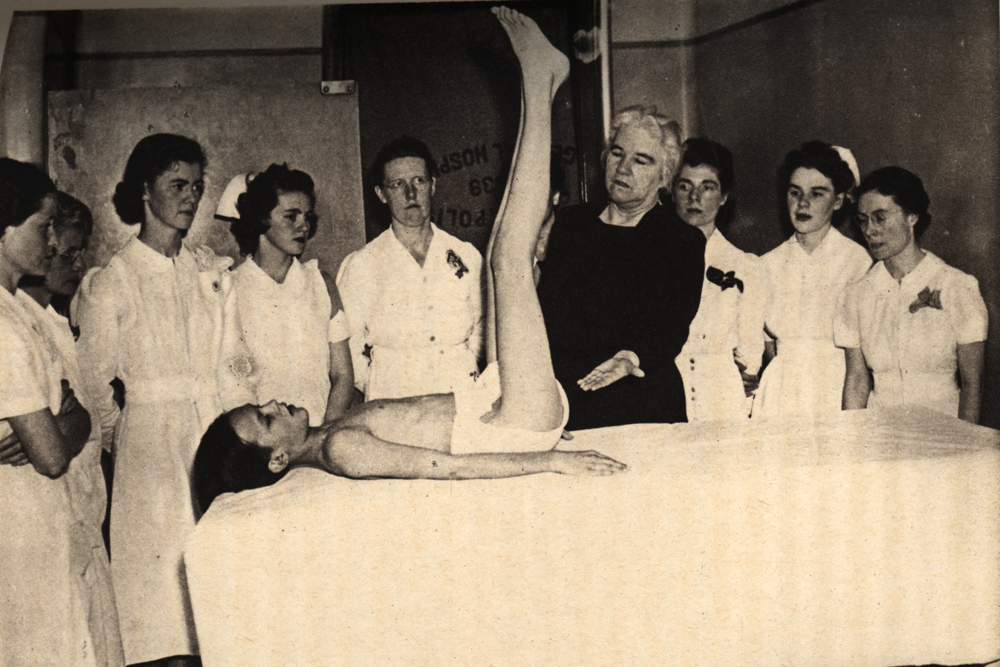

Working as a “bush nurse” in rural Queensland, Sister Kenny had never heard of the established treatment for polio. Relying on keen bedside observation, she experimented with ways to alleviate a child’s muscular pain and contracted limbs. She wrapped arms and legs in hot woolen cloths and encouraged active movement of the muscles. She also made her patients learn the names of their affected muscles and how they worked—encouraging them to take an active role in their recovery.

By 1933, Sister Kenny was convinced that her methods worked. She traveled throughout Australia and England to demonstrate her techniques, but hit a wall; she had no scientific basis for her therapy. She recalled in her 1943 autobiography, And They Shall Walk: “I was wholly unprepared for the extraordinary attitude of the medical men in its [sic] readiness to condemn anything that smacked of reform or that ran contrary to approved methods of practice.”

But Sister Kenny apparently made up in will power whatever she lacked in formal medical training. Newsweek described her, rather unflatteringly, as “a human tornado.” Imposing and irascible, Sister Kenny persevered, arriving in the U.S. in 1940 to present her controversial method to American physicians and nurses. Doctors in New York and Chicago showed her the door. At the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, however, the “Kenny Method” became widely accepted. In 1942, the Sister Kenny Institute opened in Minneapolis to treat polio patients and it remains a prominent center for rehabilitation treatment and research.

This #FlashbackFriday brought to you by the @BjoringCenter for Nursing Historical Inquiry, with special thanks to @AAHNursing president Arlene Keeling, UVA professor emerita, whose book A HISTORY OF PROFESSIONAL NURSING (Springer: 2018) provided the background for this post.