Flashback Friday - Practice Makes Perfect: The History of Simulation

These days, nursing students take it for granted that technology is embedded in their curriculum. High-fidelity simulation with scripted pre-briefing and post-simulation debriefing sessions are integral to their clinical training. At UVA, a major expansion of the Mary Morton Parsons Clinical Simulation Learning Center—nearly doubling its footprint—will accommodate even more high-tech simulation.

While sophisticated technology and high-fidelity simulators are a fairly recent innovation, the concept of simulation has been part of traditional nursing education programs for more than a century.

In the post-World War II period, simulation took on new relevance; increasing complex health care services demanded more preparation and practice.

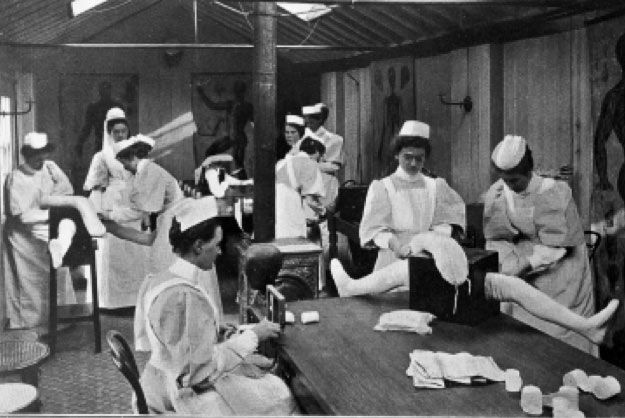

It began with anatomical models and task trainers in the mid to late 1800s. Nurse trainees used limb models to practice bandaging, bathing, and mobility needs. Demonstration rooms housed the models and gave them room to work on techniques, with a focus on psychomotor skills.

The first mannequin appeared in 1911, designed by doll maker Martha Jenkins Chase for the Hartford Hospital Nurse Training Program in Connecticut. This advanced mannequin— aptly named “Mrs. Chase” —allowed students to practice fundamental skills on an adult-size model. In short order, nursing schools across the U.S. and internationally adopted Mrs. Chase dolls, and its manufacturer later created a “Baby Chase” for obstetrics and infant-care demonstrations.

By the 1920s and 1930s, nursing arts laboratories provided classrooms with practice equipment, mannequins, and demonstration rooms. They became the mainstay of nursing school practice laboratories for the next 80 years.

In the post-World War II period, simulation took on new relevance; increasing complex health care services demanded more preparation and practice. The need for competent, experienced nurses grew exponentially with the expansion of hospitals under the 1946 Hill-Burton Act. Nurses were continually pressed to learn how to use new technology, dispense new medications, and care for patients with complex needs. But all this couldn’t be adequately learned on the hospital wards. Nurse training programs had to rely on demonstration, mannequins, and task trainers to bridge the gap.

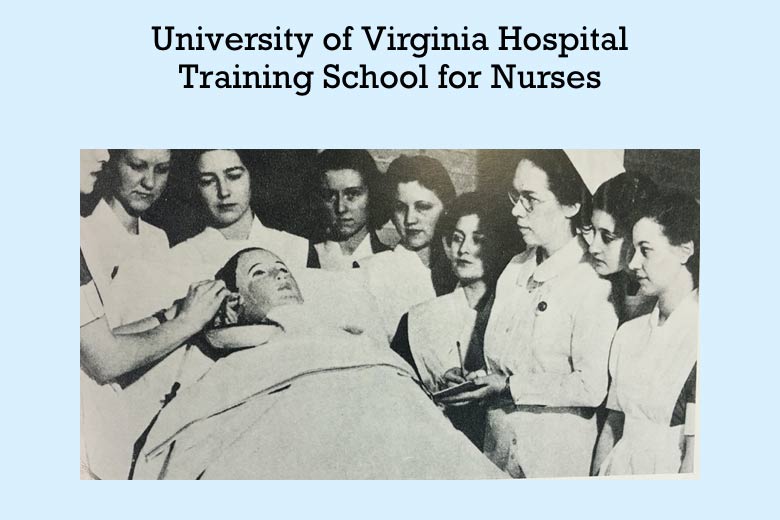

When UVA established its BSN program in 1950, it marked a major transition in how nurses were educated. Although incoming nursing students continued to receive the majority of their training on the hospital wards, the BSN program now required a six-month pre-clinical experience—to include theory and nursing skills— before a student could set foot in the hospital.

Advances in medicine and increasing specialization in the 1960s and 1970s heightened the demand for advanced nurse training. Nurses needed to learn new skills in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cardiac monitoring to carry out life-saving therapies. Simulation now meant repeated practice on resuscitation mannequins, plus role playing and interactive case studies.

The first computerized mannequin, Sim One, was developed in the late 1960s at the University of Southern California, but the technology was prohibitively expensive for most health-care training programs. A more affordable option emerged in 1968, when a life-like simulator called Harvey went into production. Many UVA medical and nursing students trained with Harvey, which could make realistic heart and lung sounds.

In the early 1990s, nursing practice labs like UVA’s morphed into learning resource centers. Students developed confidence and technical ability through repeated practice. They were encouraged to reflect on their clinical knowledge and demonstrate their competence through role play and simulation, using low-fidelity mannequins.

In 2001, Laerdal engineered the first fully automated life-like SimMan. This new simulator enhanced the ability of medical and nursing faculty to recreate real-world situations in the safety of the learning lab. UVA was an early adopter of SimMan. (And by 2006, Virginia boasted more simulators than any other state.)

A 2014 national study that compared traditional clinical training to simulation suggested that up to 50% of traditional clinical time could be replaced by simulation. Based on this landmark study, the Virginia Board of Nursing revised the standards for simulation in nursing education, allowing a certain percentage of robust simulation with debriefing to serve as the equivalent of direct patient care.

Source: Excerpted from “Where Role Play Meets Reality,” by Sarah Craig, PhD, RN, CCNS, CCRN-K, CHSE, and Bethany Cieslowski, DNP, MA, RN, CHSE, presented at the 2019 American Association for the History of Nursing conference.