News

October 9, 2020

Flashback Friday - All Hail the Midwife

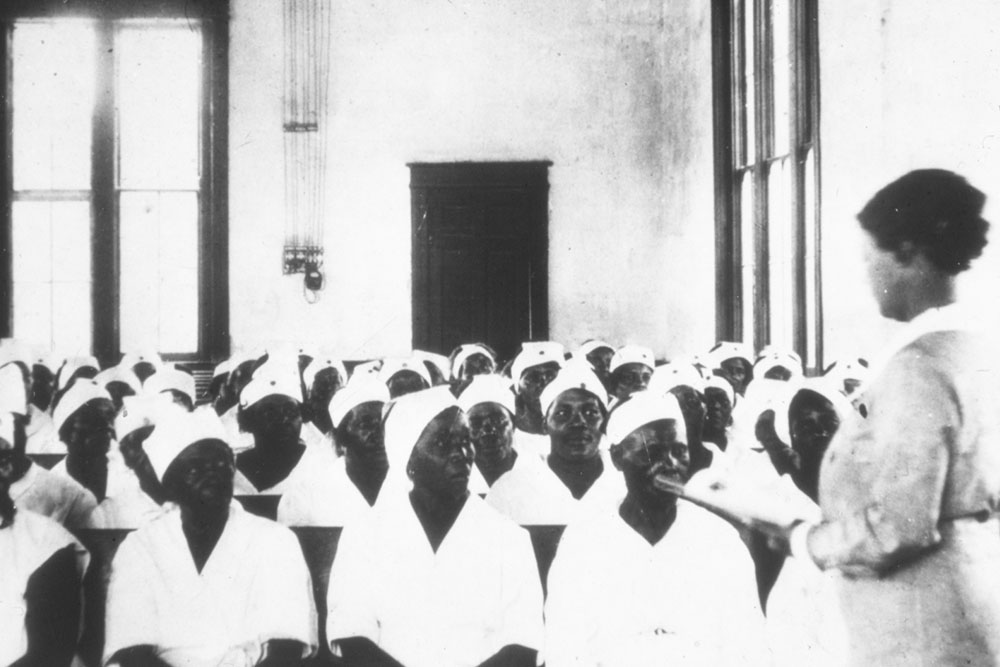

Public health nurse Eliza Pillars teaches a group of Mississippi lay midwives in 1929. From the Benoist Collection in the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry.

Birth in the United States in the early 20th century was a dangerous proposition. The country’s maternal and infant mortality rates were highest in the developed world due to a number of factors, including unnecessary interference by obstetricians—who sometimes anesthetized laboring women and removed their babies with forceps—hemorrhage, malnutrition, and puerperal fever caused by streptococcus pyogenes.

In 1915 America, 600 mothers died for every 100,000 births; by 1920, 900 women died for every 100,000 births. And perhaps nowhere was the issue more acute than in Mississippi.

80%

In 1930, 8 in 10 midwives practiced in the South

Caroline H. Benoist, Mississippi-born and a 1925 graduate of Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, became one of the first public health nurses in her state. Self-directed and creative, she established a prenatal program in Pike County in 1936 to assist physicians with home deliveries and teach best practices to “Granny” lay midwives.

Benoist’s collection of papers, letters, and photographs—housed in the Eleanor Crowder Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry archives—offers a rich historical narrative about public health nursing in Mississippi in the 1930s, and a lens on rural midwifery practice and communicable diseases. Through Benoist, we see how race, class, and gender in healthcare intersected at a particular place and time.

In 1930, more than 80 percent of midwives practiced in the South, where a quarter of all babies—and half of Black babies—were delivered by mostly Black lay midwives. Mississippi had about 5,000 midwives, double its number of physicians, and the majority of births occurred at home. Benoist knew that these midwives, trained through apprenticeship and experience, were key to reducing Mississippi’s childbirth-associated mortality. Investing in their education meant better health for Mississippi mothers.

In 1930, 80% of midwives practiced in the South. In Mississippi alone, there were 5,000 mostly Black midwives at the turn of the 20th century, twice the number of physicians.

0/6

Caroline Benoist, Mississippi's first public health nurse, partnered with lay midwives to develop educational programs to reduce the incidence of maternal mortality, which was high.

1/6

Investing in and furthering their education, she knew, would be key to reducing mortalities among mothers and infants. Here, midwife Eliza Pillars teaches a room full of lay midwives.

2/6

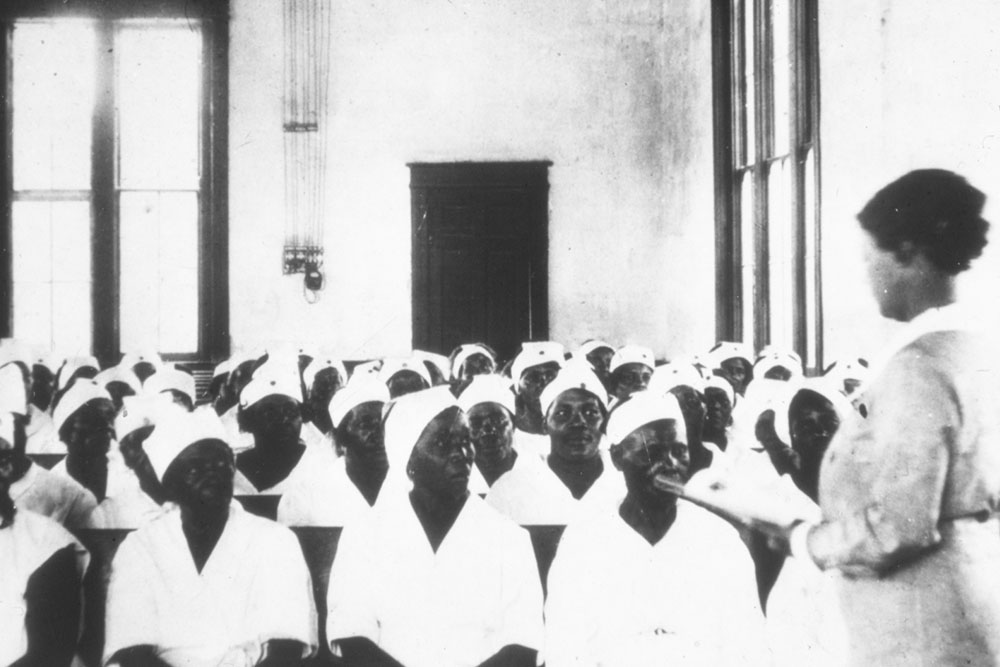

Benoist and her midwife and public health nurse partners created systems to improve giving birth at home. Here, she outlined a list of what items a midwife should include in her nursing bag.

3/6

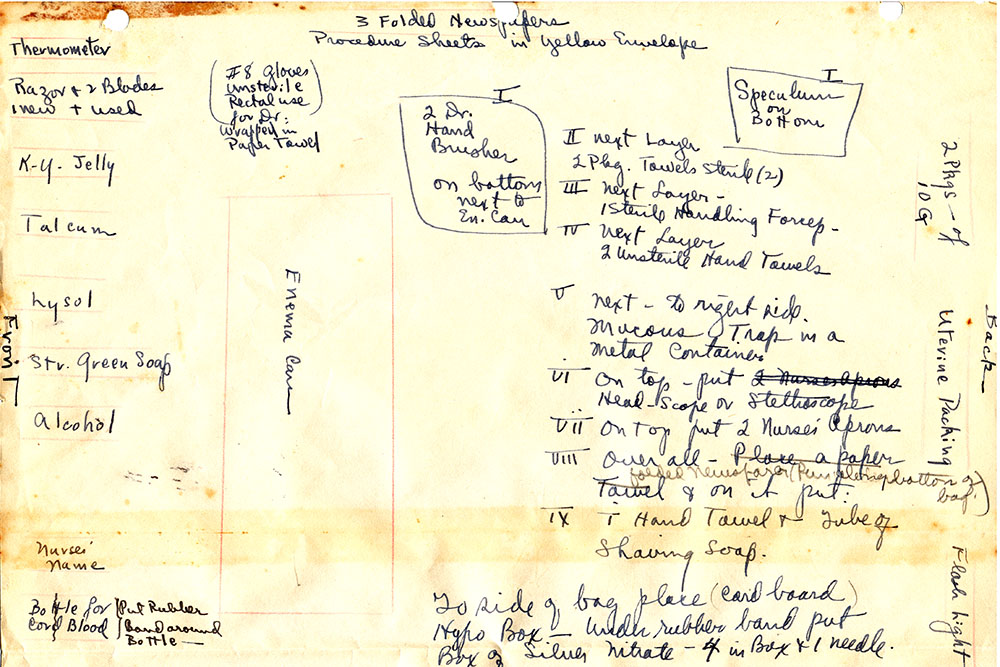

Benoist even developed plans for a warming box for infants born premature in need of extra care and comfort.

4/6

The work changed the infant and maternal mortality tide, and affirmed the roles mostly Black midwives played in that change. Here, three generations of midwives pose for a picture.

5/6

Such partnerships helped turned the tide. Between 1921 and 1942, maternal mortality fell by more than half, and infant mortality declined 40 percent. In this, the Year of the Nurse and Midwife, we pay homage to these women, their partnerships, and the progress they made together to celebrate and preserve the unique professional role these African-American women had in their communities.

Today's #Flashback Friday brought to you by the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry, and comes with a salute in this, the Year of the Nurse and Midwife.