Compassion in the Crevices

From the Richmond Times Dispatch Sunday Commentary, Dec. 16, 2017:

Compassion in the Crevices

By assistant professor Tim Cunningham

You’ve seen them, the iconic images of American soldiers dressed in fatigues and combat gear, cradling small, injured, sometimes bloodied children. Of firefighters heading toward danger to save lives. Of fisherman in modest sea vessels lifting exhausted, near-drowned refugees from the freezing Mediterranean. Or even, here in my hometown of Charlottesville, Virginia, the quiet grace and competence of nurses capably tending injured white supremacists last August across the rising tide of politically inspired violence.

Compassion, all of it, on a grand and overwhelming scale.

Often confused with empathy (the experience of feeling someone else’s pain), compassion occurs when you recognize someone else’s suffering, accompany them as they suffer, and then do something about it. As a nurse, I’ve had the privilege of working with some extremely compassionate people in immensely challenging geographies – in post-earthquake-ravaged Haiti, in Ebola-stricken West Africa, even in parts of the Middle East that remain among the world’s most unsettled and violent locales.

It is big, life-changing work that often makes compassion as a practice seem out of reach, or impossible to incorporate for the average human hoping to do good. Especially in an era when we’re told we’re more divided and more isolated than ever, compassion can seem a fleeting phenomenon. Yet, I’m learning through my own research that compassion happens far more often than we think – and detecting it, and benefiting from it, has a lot to do with how we define it.

All too often we consider compassion in the extremes: when lives are saved heroically or when large cash donations are made (think professional football players like Colin Kaepernick and Chris Long). I believe that most of the world’s compassion is conducted quietly, in small doses, rather than in awe-inspiring, sweeping heroics – and that, as a result, the world is a far, far more compassionate place than most of us realize.

The small doses theory certainly holds true in nursing and medicine. It’s compassion when your nurse places her hand on your shoulder while listening to your heart beat. When your physician sits on the corner of your bed to give you a diagnosis. When, before giving a child an injection, the clinician urges a laugh, or proffers a hug when it’s all over. But it’s true elsewhere, too.

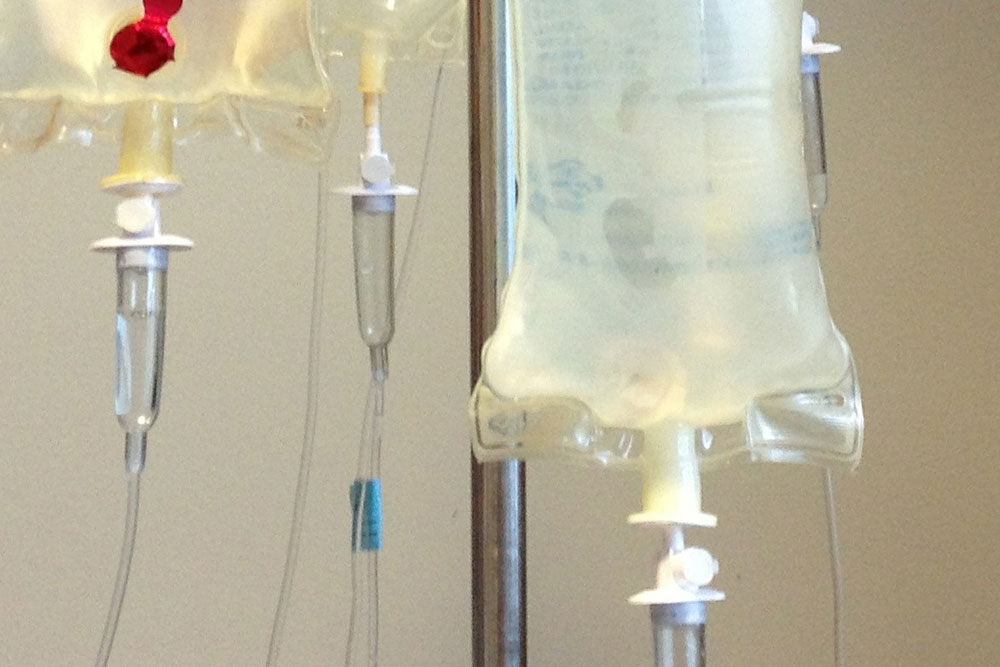

Holding open a door for someone, clutching the hand of a friend, hugging your grandmother for two seconds longer and with extra squeeze before goodbye – that’s compassion. In my own research with nurses and doctors, they consistently reveal that compassion comes like an IV, in small drips, in digestible doses. It happens moment by moment when people first recognize that someone else is suffering, and that they can do something about it. Period. Their actions do not have to be grandiose.

And it’s good for us, too. Research shows that compassion changes the brain, lighting up neural pathways associated with good feelings, joy and love. That people who are repeatedly compassionate actually strengthen these compassion-related brain regions, and report higher satisfaction in life and happiness. And that compassion is as good for the recipient as it is for the giver: you.

Yes, compassion comes from heroes, but far more frequently it comes from regular people like us that do one small kind thing to make someone else smile. In this season, at this time of year, in this particularly unsettling period when more can seem wrong than right, notice those moments. Celebrate them, these bits of compassion in the crevices. And understand that your small gestures form a bedrock layer of goodness against which our world and all of humanity can lean.

+++

Tim Cunningham, RN, DrPH, an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Virginia School of Nursing, is director of the School’s Compassionate Care Initiative and a former ER nurse, professional clown and actor.