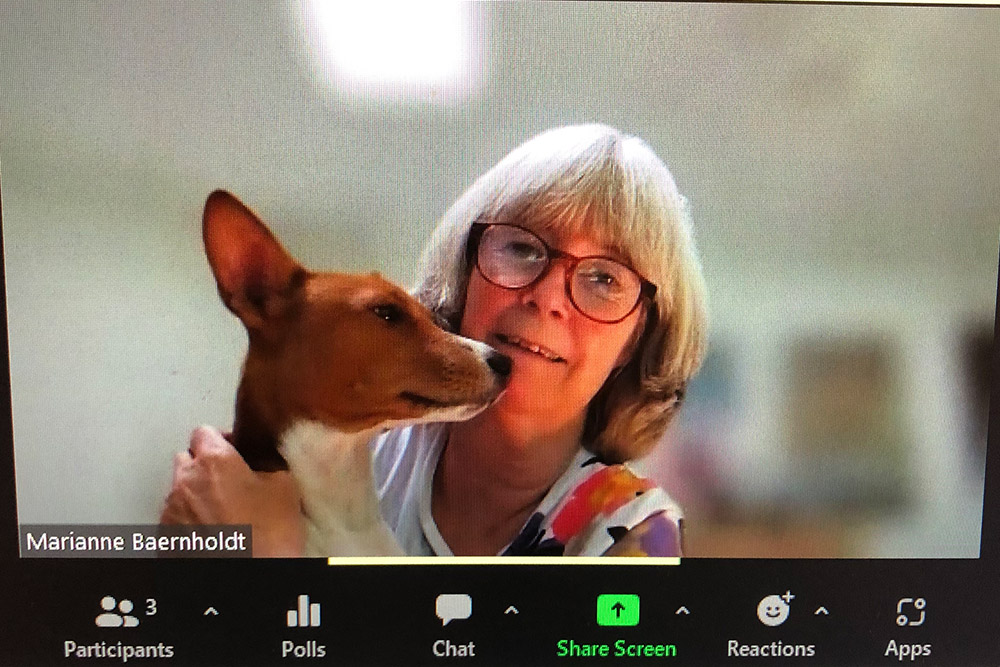

Dean Marianne Baernholdt: A Leader from the Beginning

Marianne Baernholdt returned to the School of Nursing to take the dean’s reins on Aug. 1, but has been a leader from her earliest nursing days.

As a 19-year-old student in her native Copenhagen, Denmark, she was tapped as a leader for the first time, she told the School in her first address. “Dannerhuset,” built as a women’s shelter in the late 1800s by the Countess Danner, was threatened with demolition by the late 1970s. Baernholdt was one of a handful of leaders who guided a group of about 300 women who saved the shelter through activism and fundraising. Thanks to their efforts, Dannerhuset remains in operation today, more than 40 years later, and a symbol of Danish feminism.

Baernholdt—a nurse scientist for 20 years, an educator and mentor for 30, and a nurse for nearly 40—sat down with UVA Today to talk about everything from nurse burnout to health care equity to the national nursing faculty shortage.

Being an immigrant myself also colors how I connect with others: It really is about finding common ground. So many of the problems we face begin at exactly that point.

Dean Baernnholdt, on her global focus

Q. You were on the UVA nursing faculty from 2005 to 2014. What brought you back?

A. Because it’s UVA and because of the people! Many faces at the Nursing School are beloved to me, and the variety and strength of our research and our across-Grounds collaborations are exciting, too.

The opportunity to be part of decisions that influence healthcare delivery and working conditions for healthcare workers was a powerful driver to return as well, as it is in line with my life’s work.

Today, there’s a sense of new energy, and synchronicity with the health system. UVA Health is more a part of the University, and feels more proximate and connected to the school, its faculty, staff, and students. I report to both the provost and to the executive vice president for health affairs, which feels right and important. For a nursing dean, the role really is the total package.

Q. What are challenges facing nurses and nursing education?

A. COVID gave the world a better sense of what nurses do and has given us a platform to speak up in ways, perhaps, we’ve never done before. Of course, COVID also gave us a look at what happens when nurses don’t get what they need, and the ways our systems need to improve. My research focuses on how to ensure our frontline workers are safe, supported and whole, and have what they need to care, thrive, and stay.

Nursing education has some big challenges in front of it, in addition to the overall shortage of bedside providers. Just 1% of nurses ever earn a PhD in nursing and become academics and scientists. That means there are far too few people to teach the students who are applying in droves, especially to our undergraduate programs. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing tells us that about 80,000 qualified applicants a year are turned away from undergraduate nursing programs across the U.S. because there are too few faculty members and not enough space to teach them. That is a steep hill to climb, but it starts with attracting more nurses to programs like the PhD and DNP (Doctor of Nursing Practice). Too few of us do that.

We also need to make it easier for nurses to consider graduate study in the first place, to really show them the benefits so they can see the undeniable value in furthering their education: how it will change their perspectives, professional trajectories, their pocketbooks—and their patients’ lives.

Q. How do you plan to address the nursing shortage?

A. COVID drove many nurses to quit, but the exodus was happening long before the pandemic. Many nurses felt and feel overworked and underpaid, exposed to high-acuity situations without adequate protection and supplies, and continuously asked to work in high-stress work environments. But in my own and others’ research, it’s abundantly clear that if the well-being of nurses and other clinicians is high, patients’ outcomes—and hospitals’ outcomes—are much better. So we all have a stake in keeping nurses feeling whole and supported.

UVA has made many positive changes to this end, such as improvements in pay. But it’s a matter of continuous improvement here and around the world. The will to improve is there.

Addressing the shortage requires a road map for our School and, to that end, we’ve begun a strategic planning process that pulls from UVA Health’s plan, builds on President Ryan’s “great and good” model, and is also deeply informed by our own IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, and Excellence Achievement) initiative. The vision we create will set our path forward.

We need to make it easier for nurses to consider graduate study in the first place, to really show them the benefits so they can see the undeniable value in furthering their education: how it will change their perspectives, professional trajectories, their pocketbooks—and their patients’ lives.

Dean Baernholdt

Q. How will your expertise in global health influence your deanship?

A. My global lens is not one I can turn off. It’s always with me, and that’s a good thing. I have traveled with countless students all over the world and met nurses from so many continents and countries, experiences that inform who I am and what I do. Being an immigrant myself also colors how I connect with others: It really is about finding common ground. So many of the problems we face begin at exactly that point.

It’s exciting to me, too, that global programs are returning. Last summer, 11 nursing students studied in Kigali, Rwanda; and Roatan, Honduras, traveling with faculty members who have long-term partnerships in those countries. Nothing can replace those kinds of experiences and perspectives. Our curriculum, even though it’s packed with skill, science and real-world assessments, intentionally makes room for such experiences. That is as it should be.

I am often reminded that nursing is much the same across the world, despite differences in resources and cultures. We all care for patients, their families, and communities across the lifespan. Many of the challenges we face are the same, too, so we must learn from each other.

Q. Can you tell us a little about your family?

A. My husband, who grew up in California and Denmark, is a retired physician. We have three grown children who grew up in the United States: a daughter, who lives in Oregon and is a nurse; and two sons, who both live in Denmark.

We have two dogs: Zero and Taz. They are Basenjis, a very independent breed, which is another word for untrainable. Sometimes that shows. They are inveterate Zoom bombers.

Q. What’s your favorite thing, or one of them, about being back at UVA and in Charlottesville?

A. Besides Bodo’s and Gearharts Chocolates? The good restaurants! Eating aside, I love seeing the mountains every day as I drive to and from work. And walking around Grounds.

###