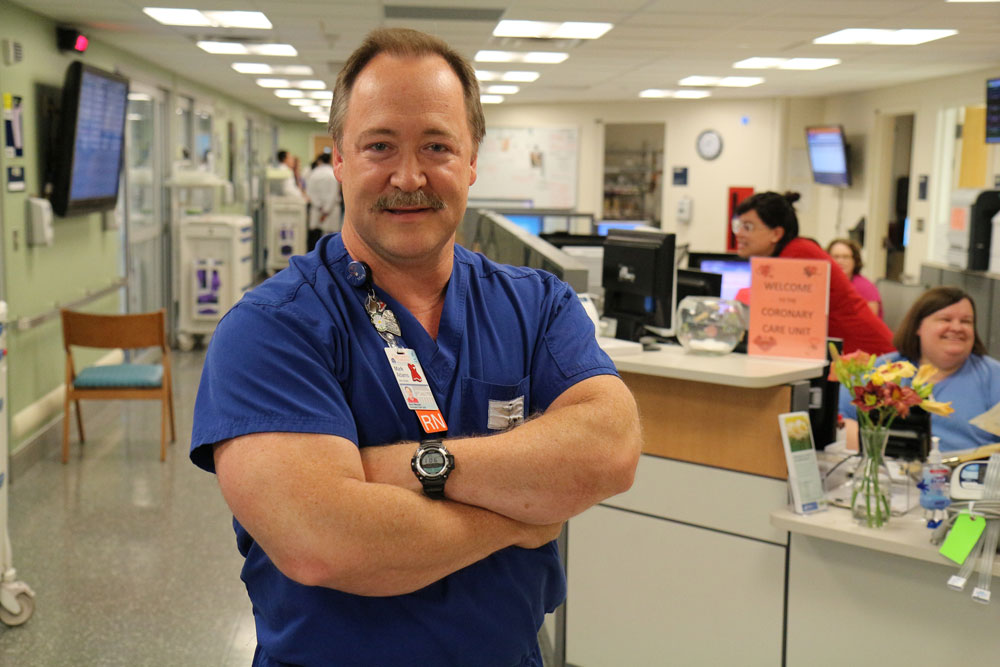

Cool Care, Warm Heart: Alumnus Mark Adams, BSN `97

Although Mark Adams’ (BSN `97) path to nursing wasn’t always clear, looking back, he sees clues in each twist and turn along the way. His mother, a nurse for 35 years, shared stories of her work, and Adams, rapt, spent hours poring over her nursing manuals.

“I was always interested in CPR and first aid as a Boy Scout and lifeguard, and later as a volunteer paramedic and a teacher,” Adams says. “With each step, I gained a new skill that led me to where I am today.”

After earning a degree from UVA’s Curry School of Education in 1984, Adams worked as a special education teacher for several years before becoming the executive director of Central Shenandoah Emergency Medical Services Council. A certified paramedic, Adams also volunteered for the Western Albemarle Rescue Squad for 15 years.

“Medical service was always in the background of my life,” even before enrolling in the School of Nursing’s second-degree program in 1995, Adams recalls. After graduating from the BSN program in 1997, he began working in the Coronary Care Unit (CCU) at UVA, where he’d done clinical rotations as a student.

Today, Adams is nurse manager of the CCU and program coordinator of UVA’s Therapeutic Temperature Management Program, which offers high-tech cooling by catheter for patients who have experienced a cardiac arrest. Now nearly a decade running, the program transitioned from using strategically placed bags of ice to lower the body temperature to, today, using refrigerated saline, delivered by catheters to carefully lower patients’ body temperature and thereby stabilize body and brain function.

The results, says Adams, are nothing short of dramatic.

“[Before this technology], in my first nine years, I recall only one person leaving the CCU alive, with normal brain function, after being resuscitated from cardiac arrest,” Adams recalls. “We started cooling patients with ice packs and cold blankets and got much better results; now we use intravascular cooling catheters. Cooling the patient stops the deterioration of brain function. Without it, between two and ten percent of patients survive. Now, up to a full third do.”

Adams, who formed the Therapeutic Hypothermia Task Force to research available cooling equipment, guided UVA Medical Center’s equipment purchase in late 2007. Since then, patients who have a cardiac arrest outside the hospital who arrive at UVA have much greater chance of leaving the hospital, and resuming normal life.

Adams’ favorite part of his work is what he calls the “who’s in there” moment when his team, after rewarming the patient, weaning off medication following the cooling process and removing the breathing tube, finally has the chance to talk to the individual in their care.

“I love it when we get to find out who’s in there,” says Adams.

###